Memories of the Panama Invasion Rekindled as U.S. Deploys Warships to Caribbean

The Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyers, USS Preble, USS Halsey, and USS Sampson, under way in the Arabian Gulf.

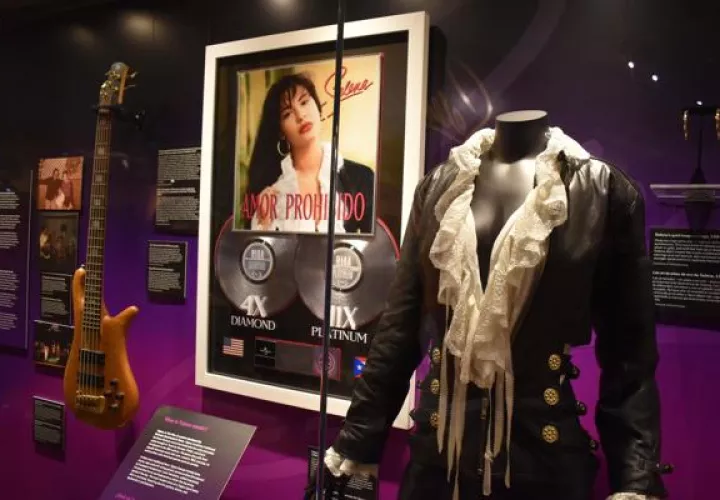

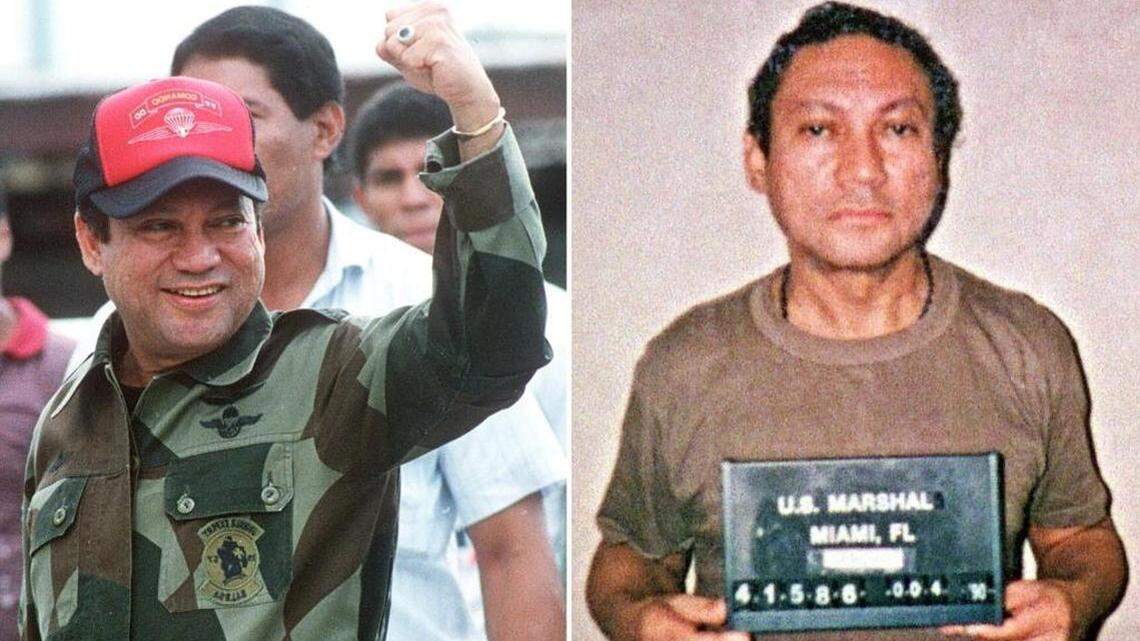

As three Navy destroyers and three amphibious warships move toward the coast of Venezuela this weekend in an ostensible U.S. counter-narcotics operation, the Trump administration’s show of force is rekindling memories of another presidency, era and country. In mid-December 1989, President George H.W. Bush ordered a military invasion of Panama, saying its strongman leader, Manuel Noriega, a one-time American ally and CIA informant, was a threat to U.S. interests in the Canal Zone and a corrupt general wanted on drug-trafficking charges for turning his country into a narco-state for Colombian cartels. During Operation Just Cause, the U.S. troops not only used force but blasted rock music, including songs by the band Guns ‘n’ Roses, as Noriega took sanctuary in the Vatican Embassy in Panama City.

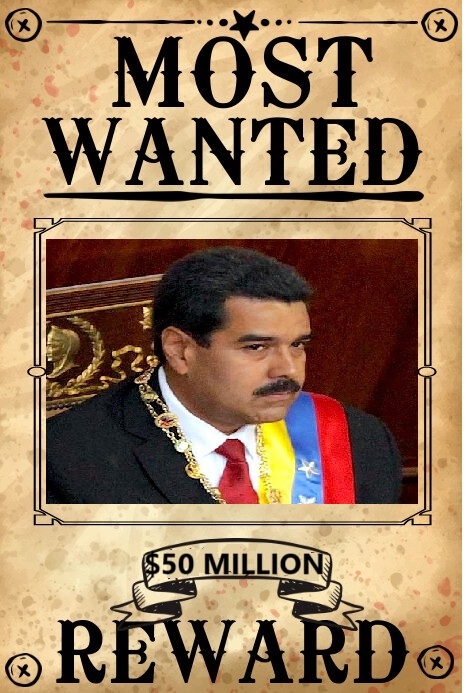

He surrendered on Jan. 3, 1990, and was whisked away to Miami, where he would later stand trial, be convicted and spend about 20 years in prison. Two South Florida lawyers — one who charged Noriega and another who defended him — say that it may look like President Donald Trump has ripped a page out of the Panama playbook as U.S. Naval forces veer toward Venezuela. But attorneys Richard “Dick” Gregorie and Jon May point out there are similarities and differences between then and now. They also say it’s unlikely that Trump, who has an avowed aversion for committing U.S. troops in warfare around the globe, would risk invading a country the size of Venezuela. Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, like Noriega at the height of the U.S. war on drugs, was indicted by a New York grand jury on drug-trafficking charges in 2020.

But Maduro is the leader of an oil- and mineral-rich country that, despite its economic troubles, is far larger and more powerful than Panama. Moreover, Maduro doesn’t exert the same degree of control over his military as the Panamanian dictator did over his forces in the 1980s. “There’s a big difference between the situations that were going on in Panama at the time than what is going in Venezuela,” Gregorie said in an interview on Friday. “There’s something else going on [other] than drug trafficking,” added Gregorie, who worked as a high-level federal prosecutor in Miami and other parts of the country for more than 40 years before his retirement in 2018. “That’s not the reason why Trump is sending those ships down there.

“There’s more going on and intelligence that I don’t have access to,” he said, noting Venezuela’s ties to Iran and the South American country’s substantial mineral resources. May, who along with attorney Frank Rubino defended Noriega at his 1992 trial in Miami, agreed with the former prosecutor, saying that while Maduro and Noriega seem like similar targets as accused drug traffickers in the United States, invading Venezuela would be foolish. “I can’t imagine the United States invading Venezuela – other than the crazy factor,” May said, noting that Trump’s sending the fleet of destroyers and warships to Venezuela is a “modest” mission, but perhaps “just enough saber rattling” to help him and the Republicans in the midterm elections next year.

“It was really easy for the U.S. military to crush Panama,” he said, “but it would not be the same thing in Venezuela. You have a highly motivated army in Venezuela that would provide stiff resistance. It would be suicidal.” Another major difference: Even before the American invasion of Panama in late 1989, the U.S. military already had more than 12,000 troops stationed at bases in the Central American country, plus warships, planes and vehicles. The Pentagon estimated that more than 500 Panamanians were killed during the invasion, including more than 300 soldiers and 200 civilians. A total of 23 U.S. soldiers and three U.S. civilians were killed.

The United Nations General Assembly, the Organization of American States and the European Parliament condemned the invasion as a violation of international law. Indeed, using U.S. forces to invade Panama and capture Noriega in a law-enforcement operation in a foreign country was highly controversial at the time. Once Noriega surrendered and no longer posed a threat to U.S. interests in the Canal Zone, the U.S. military turned him over to federal agents. “There was no basis for our military to hold him as a prisoner, which is why he was turned over by the Marines to the DEA on the flight home,” May said. Because of the legal and political complexity of the case, it took until 1992 for the U.S. Attorney’s office — led by prosecutors Michael “Pat” Sullivan, Guy Lewis and Myles Malman — to convict Noriega of cocaine trafficking and racketeering.

“It was the mother of all battles in the war on drugs,” Malman told the Miami Herald in 2010. “There was so much riding on it — the reputations of the prosecutors, the U.S. government and the president of the United States.” After the trial, U.S. District Judge William Hoeveler declared Noriega a prisoner of war who should be accorded special privileges, including an apartment-like cell — complete with phone, color TV and exercise bike — at the low-security Southwest Miami-Dade federal prison. His sentence ended in September 2007, but Noriega remained behind bars for another three years, when he was extradited to France to face money laundering charges. In 2017, he died at 83 in Panama.

Naval Fleet Headed to Venezuela

Two U.S. officials familiar with the Trump administration’s deployment told the Reuters news agency that three Navy warships — the USS San Antonio, USS Iwo Jima and USS Fort Lauderdale — could be stationed off the coast of Venezuela as early as Sunday. Together, the ships are carrying 4,500 service members, including a 2,200-strong Marine expeditionary unit. The amphibious squadron will operate alongside three Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers — the USS Sampson, USS Jason Dunham and USS Gravely — which are designed to counter threats from the air, land, sea and even undersea simultaneously. The destroyers’ arsenal centers on a 96-cell vertical launch system that can be loaded with a mix of weapons, including Tomahawk cruise missiles for long-range land attacks, standard missiles for air and missile defense, and anti-submarine rockets for undersea warfare.

By adding amphibious vessels, the task force gains expanded land capabilities, particularly the ability to quickly deploy Marines into coastal zones. The Pentagon has not publicly disclosed the ships’ mission, but sources told the news agency that the move aligns with the Trump administration’s aims at addressing threats to U.S. national security from specially designated “narco-terrorist organizations” in the region. Speaking about the possible use of U.S. military personnel in Venezuela, the White House said that the deployment underscores Trump’s pledge to use every instrument of American power — from sanctions to military force — to stop narcotics from reaching U.S. soil.

“President Trump has been very clear and consistent: he’s prepared to use every element of American power to stop drugs from flooding into our country and to bring those responsible to justice,” said White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt after being asked by a McClatchy reporter on the chances of a boots on the ground operation taking place inside the South American nation. Cracking down on drug cartels is a pillar of Trump’s domestic and foreign policy. Earlier this year, the administration formally designated Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua gang and several other groups as global terrorist organizations. The move gave U.S. agencies expanded authority to target cartel finances, logistics and leadership.

Last month, the Trump administration designated the Cartel of the Suns — which U.S. prosecutors say is run by Maduro and other high-ranking members of his regime — as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” entity. The designation raises the possibility that the cartel could become a direct target of U.S. military action if Trump chooses. The administration also recently raised the bounty for Maduro’s capture to an unprecedented $50 million. Maduro and several of his top allies have been indicted by U.S. prosecutors for allegedly turning Venezuela into a narco-state Cartel of the Suns. Maduro has dismissed the charges as a “rotting rerun” aimed at justifying foreign intervention.

In response to the U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean, Maduro announced on Monday that his government will activate a plan to mobilize more than 4.5 million militia members across Venezuela to “defend national sovereignty.” “This week I’m launching a special plan to ensure coverage by more than 4.5 million prepared, activated, and armed militia members across the national territory,” Maduro declared during a televised event, flanked by senior commanders. He said the mobilization is needed to counter what he described as “extravagant, bizarre, and outlandish threats” from the United States.