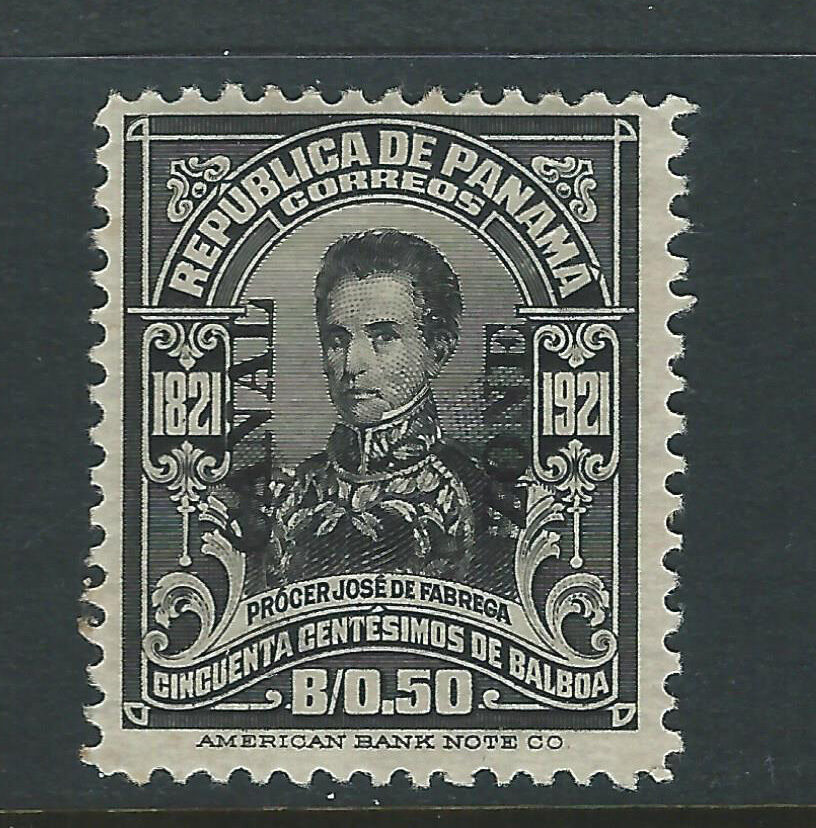

The Independence From Spain in Panama November 28. José de Fábrega Pictured Below:

Initial attempts to free Panama from Spain came from South American liberators, not Panamanians, who saw Panama as a strategic link, both politically and militarily between South America and the Central American states. As early as 1787, Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda attempted to interest the British in a canal project in Panama to increase trade for Britain, in exchange for military support to bolster South American independence hopes. The attack by Napoleon, who deposed the Spanish monarch in 1807, led to the push for independence throughout South America by Simón Bolivar. Though Bolivar did not set foot in Panama, he advocated for independence, declaring in his 1815 “Letter from Jamaica” that the independence of Panama would lead to commerce opportunities. In 1819 the Scotsman Gregor MacGregor led a failed attempt to free Panama.

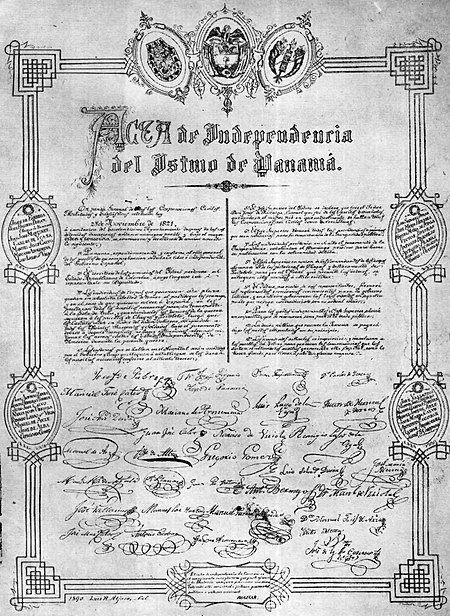

When South American revolutionary zeal deposed Viceroyalty of New Granada, Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón, fled to Panama and was declared governor. Mourgeón was ordered to Ecuador to fight the separatists and appointed José de Fábrega as his successor. As soon as Mourgeón sailed, Fábrega seized the moment for Panama’s independence. On 10 November 1821, the first call for independence was made in the small provincial town of Villa de Los Santos. Called the “Primer Grito de Independencia de la Villa de Los Santos” (Shout for Independence), it ignited rebels throughout the Panamanian countryside. Using bribes to quell resistance from the Spanish troops and garner their desertion, the rebels gained control of Panama City without bloodshed. On November 20, 1821, Fábrega proclaimed Panamanian independence in Panama City. An open meeting was held with merchants, landowners, and elites, who fearing retaliation from Spain and interruption of trade decided to join the Republic of Gran Colombia and drafted the Independence Act of Panama.

Independence of Panama from Spain was accomplished through a bloodless revolt between 10 November 1821 and 28 November 1821. Rebels in the small town of Villa de Los Santos made the first declaration for independence and the movement quickly spread to the capital. Fearing that Spain would retake the country, the rebels quickly joined the Republic of Gran Colombia. José de Fábrega, pictured above, was born October 18, 1774 and died in Panama March 11, 1841 in Santiago de Veraguas. He was a soldier, politician, statesman and neo-Granadino; (relating to, or belonging to New Granada, later called the Granadine Confederation, a country in the Americas currently called Colombia), who brought about the Independence of Panama. He was also known as the Liberator of Ismu, an honorary title given by Simón Bolivar. New Granada was the identifying name that the Spanish monarchy gave to the group of provinces whose territories today form the Colombian State, approximately the same as those that belonged to the New Kingdom at the time of Independence.

Colombia has had five names throughout its history: The Republic of Gran Colombia, New Granada, the Granadine Confederation, the United States of Colombia and the current Republic of Colombia. The name Colombia has existed for a long time, but the country has only been called that way since Simón Bolívar called the political project around the nascent and ephemeral national state of Colombia “Great Colombia.”

Panama gained its freedom from Colombia on November 3rd 1903 when Panamanians revolted and declared independence with US support; this event is often referred to as “separation” from Colombia rather than full independence.

Independence from Spain was much earlier in Panama’s history. 28 November 1821.