MEDIAWATCH- Signals of Next Great Depression?

Staff writer at The Atlantic

The American economy is reopening. In Alabama, gyms are back in business. In Georgia, restaurants are seating customers again. In Texas, the bars are packed. And in Vermont, the stay-at-home order has been lifted. People are still frightened. Americans are still dying. But the next, queasy phase of the coronavirus pandemic is upon us. And it seems likely that the financial nadir, the point at which the economy stops collapsing and begins growing again, has passed.

What will the recovery look like? At this fraught moment, no one knows enough about consumer sentiment and government ordinances and business failures and stimulus packages and the spread of the disease to make solid predictions about the future.

V-shaped rebound ?

The Trump administration and some bullish financial forecasters are arguing that we will end up with a strong, V-shaped rebound, with economic activity surging right back to where it was in no time. Others are betting on a longer, slower, U-shaped turnaround, with the pain extending for a year or three. Still others are sketching out a kind of flaccid check mark, its long tail sagging torpid into the future.

Excitement about reopening aside, that third and most miserable course is the one we appear to be on. The country will rebound, as things reopen. The bounce will seem remarkable, given how big the drop was: Retail sales rose 18 percent in May, and the economy added 2.5 million jobs. But absent dramatic policy action, a pandemic depression is possible: the Congressional Budget Office anticipates that the American economy will generate $8 trillion less in economic activity over the next decade than it projected just a few months ago, and that a full recovery might not take hold until the 2030s.

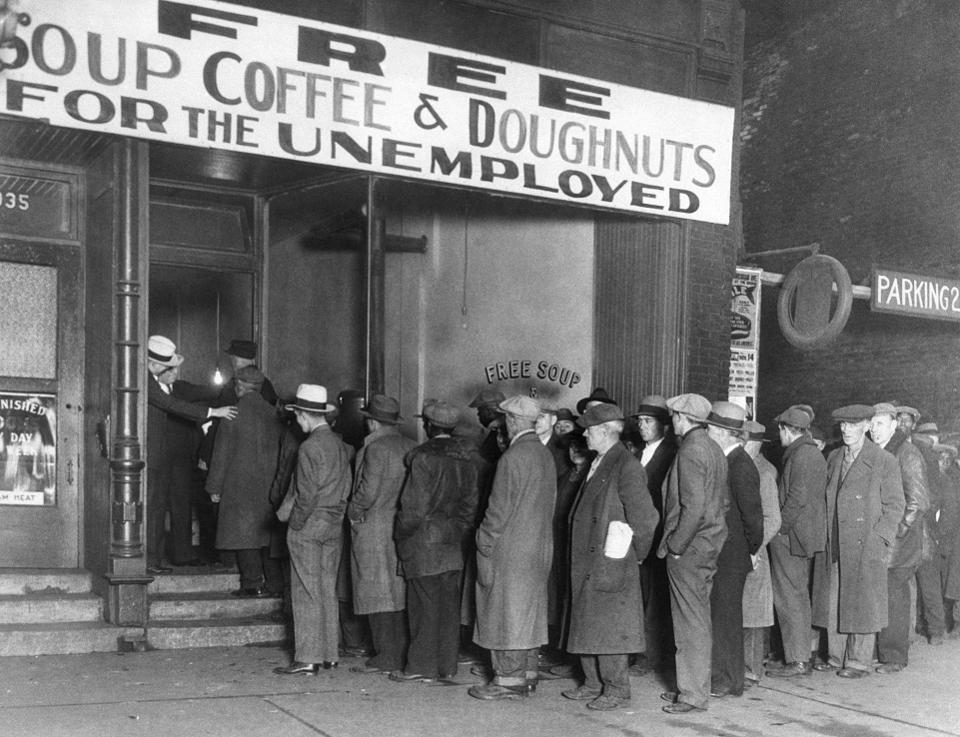

At least four major factors are terrifying economists and weighing on the recovery: the household fiscal cliff, the great business die-off, the state and local budget shortfall, and the lingering health crisis. Three months ago, the pandemic and ensuing shelter-in-place orders caused mass job loss unlike anything in recent American history. A virtual blizzard settled on top of the country and froze everyone in place. Nearly 40 percent of low-wage workers lost their jobs in March. More than 40 million people lost their jobs in March, April, or May.

Faced with this historic catastrophe, the United States marshaled a historic response: Republicans in the White House and Congress, generally hostile to the notion of economic stimulus for low-income households, came together with Democrats to achieve a $2 trillion rescue package, including a $1,200 onetime payment for most adults and $500 for many children, a radical expansion of the unemployment insurance system to include gig workers, and a $600-a-week bump to unemployment-insurance payouts. It also created a sweeping small-business rescue plan, covering payroll for companies that kept their employees on the books.

The good: This money kept families afloat—at least for the first, intense months of shelter-in-place. New estimates suggest that the congressional rescue plan prevented poverty rates from rising, with many jobless workers seeing their incomes increase during lockdown due to the expanded unemployment-insurance payouts. The bad: It left out roughly 15 million people in immigrant families, many of whom were working essential jobs stocking grocery shelves, delivering takeout, and drawing blood in hospitals. And the ugly: The big helicopter drop was a onetime thing, and the unemployment-insurance expansion was time-limited. Congress designed Uncle Sam’s help to dry up this summer, with the unemployment rate still in the double digits. Democrats and Republicans are negotiating another stimulus bill, but concerns about surging budget deficits are complicating the talks.

The cliff

That means households are headed for a cliff. But not everyone will be affected by it equally. Rich workers, the ones with do-anywhere office jobs, have remained relatively untouched by job and earnings losses thus far. Wealthy families have seen their stock portfolios rebound to close to where they were in the winter. But poor workers—disproportionately black and Latino workers, as well as younger workers—have borne the heaviest employment and earnings losses. They entered this recession with no wealth cushion, many saddled with heavy rents and heavy debts. Income and job losses for them translate into a loss of demand economy-wide, absent federal intervention.

If and when that federal intervention dries up, millions of families just keeping their head above water will sink, as lost jobs and canceled hours force them to stop paying their rent and go into arrears on their debt payments. Hunger, homelessness, forgotten plans to attend community college, babies growing up in stressed households: These are the stakes. The CBO forecasts that every quarter through the end of 2021, American consumers will buy $300 billion to $370 billion less than they would have if the pandemic had never happened.

This steep decline in consumer spending will hasten mass business failure, the second factor weighing on the economy. The Paycheck Protection Program and other federal initiatives shoved an oxygen mask on many companies. But the PPP was scaled to help businesses through a short, intense disruption, though the economy is expected to remain sluggish for months and months. Moreover, the PPP did not include much aid for businesses with significant nonpayroll overhead costs, such as restaurants in high-cost cities. This means that many businesses will fail, if customers fail to return. Already, an estimated 100,000 small companies have shut permanently.

On top of that, numerous businesses—airlines, restaurants, live-events businesses, hotels, private schools, oil and gas companies—face severe and stubborn slumps. Students are not willing to pay as much for online learning as in-person instruction. Companies are not financing travel to conferences and sales meetings. Concerts and festivals are not expected to restart until scientists develop a coronavirus vaccine. Economists expect that 42 percent of people recently let go will not return to their former employers.

A third factor behind a possible second Great Depression is the budget crisis facing states and cities. The federal government does not have to balance its ledger year to year, and perpetually spends more than it takes in. Yet every state but Vermont and most cities and towns are required to remain in the black. Right now, sales taxes, real-estate-transfer taxes, income taxes, fines and fees—they are all collapsing, leaving local governments with a budget gap expected to total $1 trillion next year. Without help from Washington, this will necessarily mean massive service cuts and job losses: namely, an estimated 5.3 million job losses.

The shrinking of the government at the state and local level has already started, as Congress dithers on providing fiscal aid. Michigan is facing a $3 billion budget gap this year and a $4 billion one next year: It has instituted a work-share plan, asking two in three state employees to accept a partial furlough. In New Jersey, the government has asked 100,000 public workers to move to abbreviated schedules. Schools have already let go more workers than they did during the Great Recession, with nearly 500,000 positions lost.

A fiscal cliff for families. Rolling business failures. A budget crisis for state and local governments. Each is bad enough. Each might be a big-enough headwind to tip the economy into recession alone. But the last element is the true alpha and omega of our worst-case scenario: the catastrophe of the American government’s management of the novel-coronavirus pandemic.

Like many of its peer nations, the United States imposed shelter-in-place and social-distancing measures to curtail the spread of the virus. But it did so late, leading to the unnecessary deaths of tens of thousands of people. And it wasted the time these extreme measures bought, because the government failed to set up a strong test-and-trace regime. Countries including South Korea and New Zealand crushed the coronavirus. The United States merely patted it down. The country is reopening with the disease still spreading and maiming and killing, as several states experience a dramatic surge in caseloads.

Never getting the pandemic under control means never unleashing the economy. Just look at the casinos in Las Vegas: open, yet half-empty. The botched response means millions of parents will need to continue watching their young children instead of committing to work.

It means thousands of offices will remain on work-from-home orders, hurting the commercial operations built to support them. It means Americans will avoid doctors’ offices, bars, and sporting events, staying at home and starving local businesses of revenue. It means localities might end up having to return to extreme social-distancing measures over the summer and fall. And it means fear and mistrust: depressed consumer confidence, ruined faith in government, and concerns about the economy’s ability to recover.

The Trump administration has repeatedly argued that there is a trade-off between the country’s economic health and its public health. But economists and physicians have repeatedly argued that that is untrue: Ending the pandemic would have been the single best thing the federal government could have done to preserve the country’s wealth, health, and economic functioning. The Trump administration, in its hubris, obstinacy, and incompetence, failed to do it.

Still, a second Great Depression is not inevitable. All four of these factors, and the many others hurting families and killing Americans, are amenable to policy solutions. Congress could extend unemployment insurance, offer new help to flailing businesses, send monthly cash grants to poor families, offer fiscal relief to the states, and implement a nationwide test-and-trace program. The collapse is over. The rebound is under way. But a terrifying future awaits us, one that does not have to come to pass.