A Renewed US Desire for the Panama Canal is Due to Climate Change

A cargo ship being escorted through the Panama Canal is pictured below. US President Donald Trump has recently threatened to take back the canal, control of which was handed to Panama in 1999, to secure US national interests. This vulnerable artery of global trade is facing increasing pressure from droughts.

The Panama Canal is one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. Up to 14,000 vessels pass through it every year. In some cases, it cuts journey times by weeks. Its importance has made it a key “chokepoint” for the global economy. This means it has attracted the attention of US President Donald Trump, who has over the past year claimed – without providing evidence – that it is being controlled by the Chinese. The US established the canal in 1904 and handed control of it to Panama in 1999. Trump has threatened to “take it back” to secure national interests. A drought in 2023 caused water levels in the canal to fall to historic lows.

As conditions worsened, Panama was forced to repeatedly reduce the number of ships allowed to pass through each day. Experts warn this is a sign of things to come, as the climate crisis combined with weather phenomena could make these incidents more frequent and pronounced in the future. Alice Hill, a senior fellow at the US-based think-tank the Council on Foreign Relations, and a former White House energy resilience advisor, says “fewer ships” passing through the canal creates a chokepoint. “If you have to divert to the Cape of Good Hope, that’s going to add weeks of travel and expense,” she explains. “It’s a shrinking asset and everybody wants a bigger part of the pie.”

The Canal and the Climate

Shipping is one of the world’s largest industries, generating annual trade worth as much as USD 14 trillion, according to some estimates. The 2021 stranding of the Ever Given in the Suez canal – slightly busier than Panama’s by traffic – highlighted how shipping disruptions cascade through the economy: the estimated cost was as much as USD 10 billion per day. The Panama Canal is a freshwater system fed by two reservoirs, the largest of which is Lake Gatún. The two lakes also supply water to Panama City and other nearby settlements. Samuel Muñoz is an associate professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern University in the US. He simulated water levels in Lake Gatún under a range of climate scenarios.

The resulting paper, published in September, says water levels will “decline substantially” over the next 75 years under “high-emissions pathways”. This highlights the “growing risk of disruptions without adaptation or emissions mitigation,” it concludes. Water levels remain relatively stable under low-emissions scenarios. Drought and low water levels tend to be linked to the cyclical El Niño weather phenomenon. Muñoz is clear that his research does not tie existing low water levels to climate change, but says it shows that a warming planet is a clear risk factor.

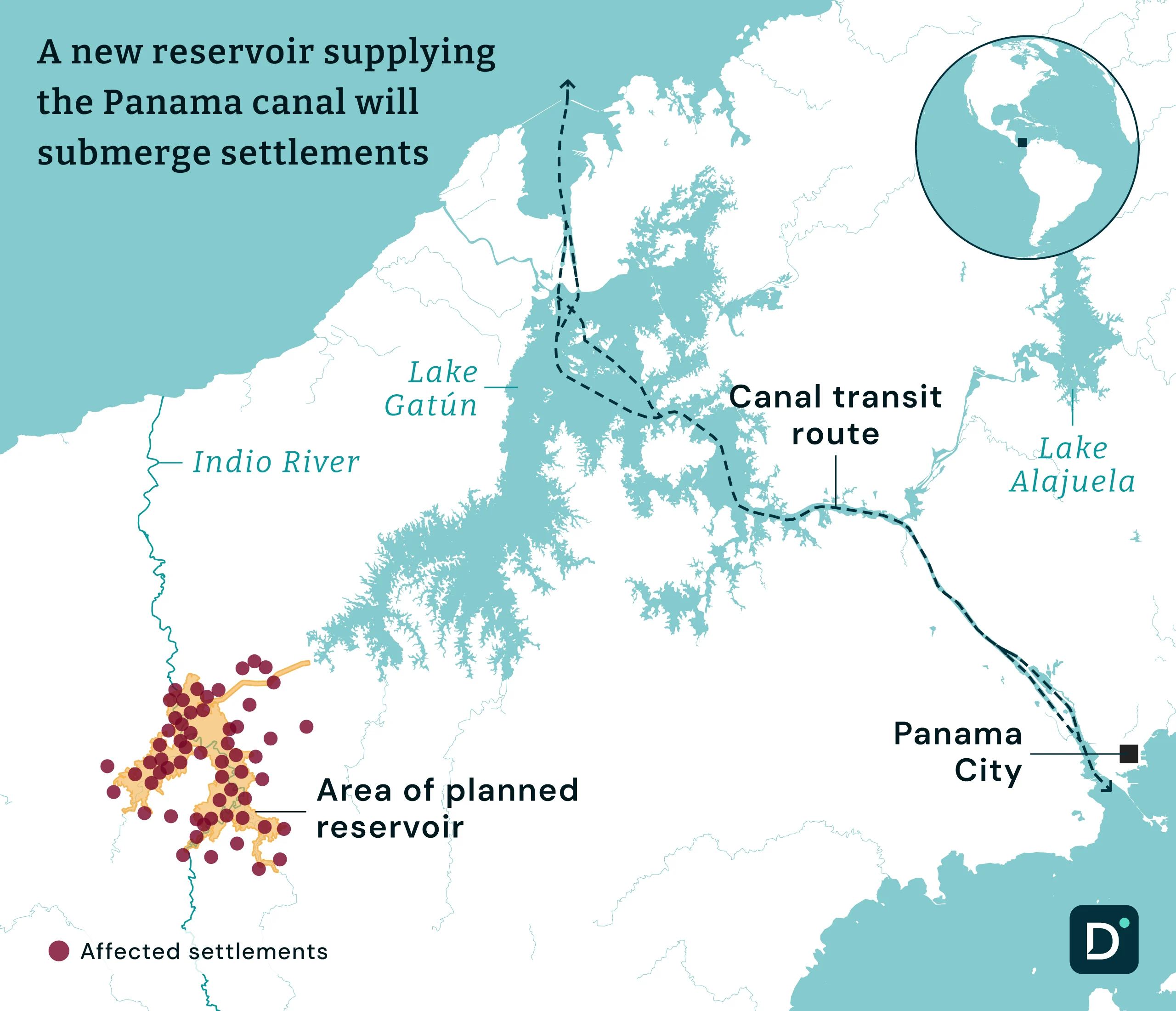

While the research] can’t say that these recent events are directly tied to climate change, it does say that the more we warm, the more of an issue this will become,” he explains. The Panama Canal Authority (PCA), which has operated the canal since control was passed to Panama from the US, has taken steps to adapt the waterway. In 2016, it opened a series of basins designed to reuse water. It will also build a third feed-in lake near the Indio River. Local residents whose homes would be flooded have opposed the plans.

Dialogue Earth asked the PCA what other climate adaptation plans are in place to secure the canal’s future but did not receive a response. Other countries have made proposals to compete with Panama. A Nicaraguan plan to build a rival waterway has stalled. More promising is a Mexican proposal to build a coast-to-coast railway line, which some experts hope could be more environmentally friendly than the canal.

The Tug of War Over Latin America

As a consequence of the canal’s importance to the global economy, the Panamanian government has found itself at the centre of Trump’s aggressive stance on Latin America and its relations with China. In recent years, China has become Panama’s largest trading partner. In November, the White House published its National Security Strategy. It laid out what has been coined the “Donroe Doctrine”, a blend of Donald and former US president James Monroe, whose 19th century policy aimed to solidify US supremacy in the western hemisphere. The strategy states that “non-hemispheric competitors have made major inroads” in the region, to “disadvantage us economically in the present, and in ways that may harm us strategically in the future”. It adds: “The United States must be preeminent in the western hemisphere as a condition of our security and prosperity.”

The following month, the Chinese government released its third policy paper on Latin America, which emphasizes its role as an ally to the region. “As a developing country and a member of the Global South, China has always stood in solidarity through thick and thin with the Global South, including Latin America and the Caribbean,” it reads. “China stands ready to join hands” with the region to “write a new chapter” based on a “shared future”. Throughout Trump’s second term, he has made clear his views on the canal’s economic and strategic importance. It has military importance, too, with US warships passing through last year amid tensions over Venezuela. Trump has described the decision by former US president Jimmy Carter to hand over its running to the Panamanians as a “bad deal”.

However, it could be argued that geography makes the canal more important to China than to the US. Christopher Sabatini, a senior research fellow at UK-based think-tank Chatham House, and founder of the journal Americas Quarterly, says: “[China] has to ship things through the canal to get to Brazil, for example. It’s a geographic reality.” A changing climate has also intensified this competition, according to Hill: “I think we’re seeing globally that, as conditions change, there’s a struggle between the US and China for economic dominance. Shipping becomes so critical and Panama has certainly historically been a part of that.” In February 2025, Panama left the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese overseas development agreement.

This January, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled that a contract held by a Hong Kong company since 1999 to manage ports at either end of the canal was unconstitutional. Trump has praised that decision; the Chinese government’s office in Hong Kong called it “absurd”, and suggested Panama had “willingly succumbed” to “bullying” tactics. The decision potentially opens the door for BlackRock, the US investment firm, to complete a takeover of the ports. These efforts had previously stumbled over China’s demand that its biggest shipping firm, COSCO, have a majority stake in any such takeover. “The US has a long history in Panama and we have a president who has asserted power in very dramatic ways and, sometimes, followed through on his threats,” says Hill.

“It’s not surprising that Panama feels pressure coming from President Trump.” Sabatini says: “If there was an inappropriate level of pressure put by the US on the Panamanian government that would be a shame, because it’s a violation of the judicial independence of a democratic country. We don’t need that.” Such disputes serve to underline the vulnerability of the Panama Canal as a chokepoint in a rapidly changing world. The climate crisis is likely to make this more pronounced over the coming decades. The US has a long history in Panama and we have a president who has asserted power in very dramatic ways and, sometimes, followed through on his threats.

Our thanks to Alice Hill, senior fellow, the Council on Foreign Relations who contributed to this report. If you wish to contribute stories to NewsroomPanama.com please send them to PanamaNewsroom@gmail.com