In Monroe’s Footsteps: Panama Colombia and Grenada – Targets of U.S. Intervention in the Cold War

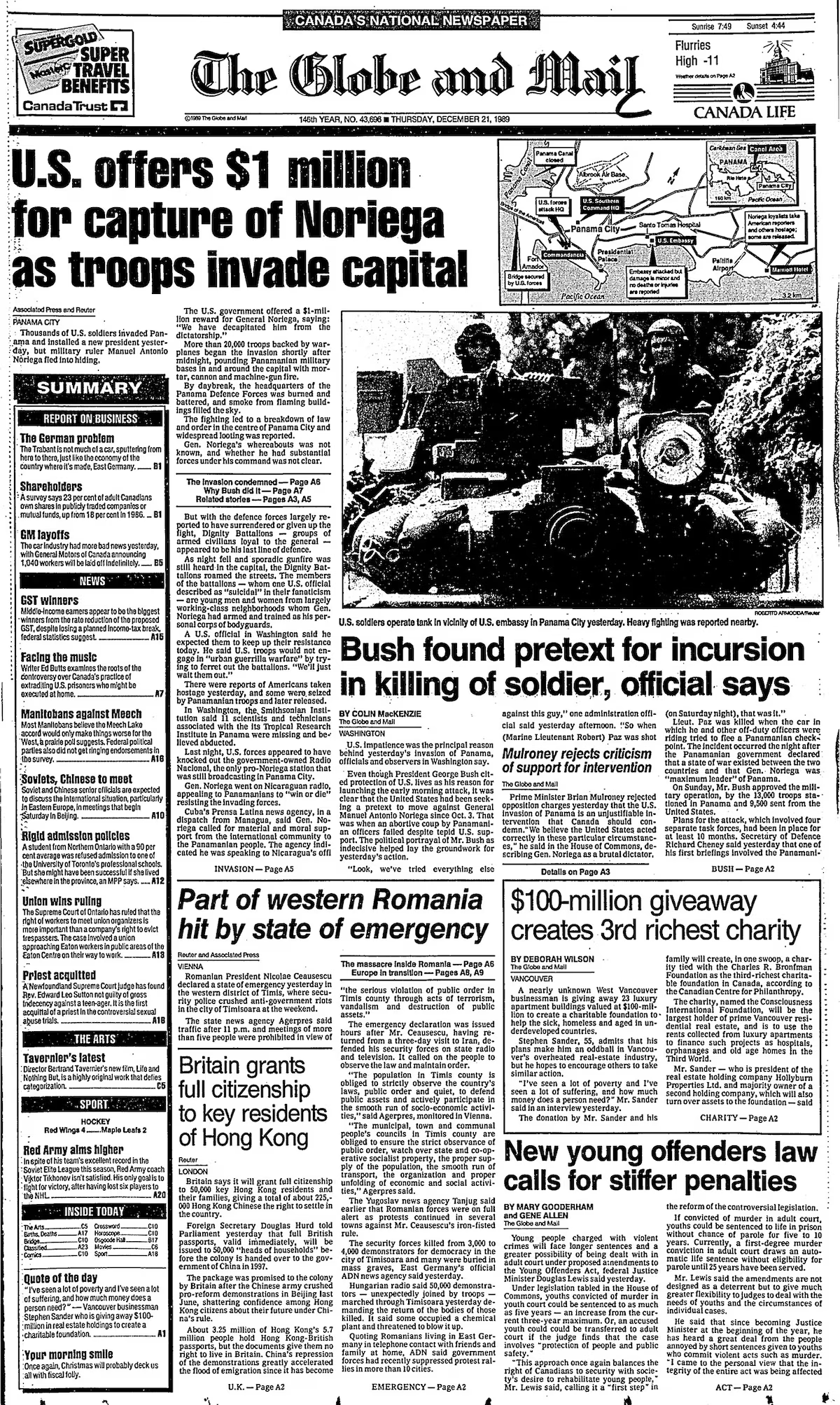

Humberto Tafur pictured below was a young man when, in 1964, U.S. backed attacks on Colombian communist fighters came to this part of Tolima department, where he still lives. In Panama, even basic facts remain unsettled, like how many people died during the 1989 U.S. invasion, was it 500 as told by the US or 5000 as calculated by Panama sources.

Humberto Tafur looks out over the steep walls of the valley that has been his home for all of his 83 years. Patches of mist dab a thick green canopy, punctuated by bursts of brilliant orange from the Cámbulo trees that are in bloom. An exuberant pulse of music echoes up from the town below, the sounds of a festival that has filled the streets with families as mounted caballistas fast-trot past. As dusk gathers, fireworks explode into the sky in flashes of light and smoke. No one flinches from the sound, not any more.

This remote corner of the country was once one of Colombia’s most violent, but many have forgotten what happened here just over 60 years ago. Not Mr. Tafur. He can still hear in his mind’s ear the sounds of May 18, 1964, the day military planes screamed into the valley, dropping bombs on the forest and the band of Communist fighters who had gathered there under the leadership of Manuel Marulanda, known locally as Tirofijo – “Sureshot” – the man who would become one of Colombia’s most famous guerrilla leaders.

In 2008, Venezuelans erected a bust of Colombian guerrilla Manuel Marulanda in 23 de Enero, a Caracas district home to vocal supporters of then-president Hugo Chávez.

Operation Marquetalia brought waves of aircraft, artillery and infantry to the valley, thousands of soldiers in multiple battalions guided through the dense foliage by Indigenous scouts to root out rebel fighters who had established their own independent republic. But the rebels quickly scattered. “That’s where the problems started,” Mr. Tafur said. Those men, and the violence they would commit, “spread throughout the country.”

Later that year, Tirofijo became a founder of what would become the continent’s most feared armed group, FARC, which grew over the ensuing decades to a force of 18,000 that controlled large parts of Colombia, earning as much as US$1-billion a year from its dominance of the country’s drug trade. “The army messed up, big time,” Mr. Tafur said. But behind the Colombian soldiers stood the military and diplomatic might of the United States, which had spent years laying the foundation for an operation that was, in turn, followed by more than a half-century of killings, kidnappings and narco trafficking by the very guerrillas it was designed to eliminate. An estimated 220,000 people died. Another 25,000 disappeared.

Operation Marquetalia is now largely forgotten, a small moment in a sprawling narrative of U.S. involvement down the length of the Americas, a history that has reached from the 19th century through to the moment its commandos seized Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro from his bedroom earlier this month. Tactically, the seizure of Mr. Maduro was conceivable only in an era of stealth aircraft and electronic warfare. Philosophically, it belonged to a much longer chronicle, the sweep of a United States that has, since 1823, openly conceived of itself as an imperial power.

That year, the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine announced Washington not merely as the capital of a country – one still so young it had yet to establish its own English dictionary – but as the heart of an empire with a reach and ambition that extended far beyond its own borders. American power would be exercised throughout the hemisphere in service of America’s corporate, political and ideological interests, a means to wage the Banana Wars and the Cold War alike.

U.S. soldiers occupied Nicaragua and Haiti. The country’s intelligence services toppled leaders and set up new ones, involved in so many changes of regime that scholars debate whether the correct figure is less or greater than 100. Its politicians deployed their military and economic might to push foreign powers from territory they alone sought to influence, seeking over the many decades to repel Spain and Britain, and then, in another age, Russia and Iran – and, now, China.

Gaitania was in a festive mood for the recent Epiphany holiday, but in 1964, this area was reeling from attacks that scattered rebel forces around the countryside. There is graffiti from one such group, FARC, along the mountain roads.

What’s old is new again. Donald Trump’s actions in Venezuela sparked an angry response in many parts of Latin America. Before ordering Mr. Maduro’s removal, Donald Trump embraced what he has called the Donroe Doctrine, an idea his administration, in a national-security strategy published last year, called “a ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine.” “This is where we live – and we’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be a base of operation for adversaries, competitors and rivals of the United States,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said earlier this month.

For Canada, still nervous after Mr. Trump repeatedly said last year that he favors annexation, this moment has raised anxiety, heightened by the speed with which the White House has already moved to redraw the global map, asserting control of Venezuela and saying it intends to take over Greenland. In Latin America and the Caribbean, too, a fresh assertion of the Monroe Doctrine has elevated fear. But in those countries, it is a fear freighted with memory. In many, the work of reckoning with past American interventions has not yet finished. In Panama, even basic facts remain unsettled, like how many people died during the 1989 U.S. invasion. In Grenada, questions continue to be asked about what happened to the bodies of former leaders after U.S. paratroopers descended in 1983. Even so, the White House is once again training its attention on what the State Department has called, in bold text, “Our Hemisphere.”

Over the past week, news reporters travelled to three of the places where the U.S. has overtly intervened over the past century, places where the long roots of its current policy found sustenance in foreign soils. In Panama, Colombia and Grenada, history offers understanding for the current moment – and, from those whose lives were torn apart, a warning. “It’s Donroe madness,” said Andrew Bierzynski, a Grenadian businessman. In the past, the U.S. couched its action in the language of promoting democratic values. Today, Mr. Trump openly covets oil and critical minerals buried outside American borders. “This is the naked fist of American arrogance,” Mr. Bierzynski said.

Trinidad Ayola lost her soldier husband when U.S. forces invaded Panama in 1989 and captured the president, Manuel Noriega. Today, Ms. Ayola advocates for Panamanians who lost loved ones.

There is still anti-U.S. graffiti in El Chorillo, the Panama City neighborhood hit hardest by 1989’s fighting. Mr. Trump’s more recent threats to seize the Panama Canal have sown more suspicion of Washington.

Gaitania and Panama City were once part of the same country, but U.S. intervention in the 1900s changed that. When Colombian lawmakers would not give Washington favorable terms for the Panama Canal, President Theodore Roosevelt tacitly backed a secession movement there.

The Monroe Doctrine emerged in a few sentences tucked into President James Monroe’s annual message to Congress in 1823. The declaration it contained was directed toward European powers, with a warning that the Americas “are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” From the outset, the doctrine embodied a paradox. The United States was born as an anti-imperial power. The doctrine amounted to an embrace of what it had rejected. But the U.S. has “always had ambitions.

Imperial Ambitions

Designs on territories in North America, control of markets in the hemisphere – resources and so forth,” said Jay Sexton, a historian at the University of Missouri who is the author of The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America. The doctrine “is about carving up the globe into spheres of influence. And it served a really useful purpose as the United States was growing in power,” Prof. Sexton said. The U.S. of the early 19th century was no superpower. The doctrine fixed an American sphere of influence, but it was a limited one. The rest of the world was left to others.

After the Second World War, however, the U.S. emerged dominant, able to project influence far beyond its own neighborhood. Its sphere became the globe. The return of the doctrine under Mr. Trump is, then, a tacit admission of weakness. “The United States is now a power in decline, and spheres of influence are back. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the doctrine is making a return as well,” Prof. Sexton said. But history has also shown that invocation of the Monroe doctrine has rarely yielded tidy results. Time and again, “intervention was the first step, and then it led to occupation. Then it led to a war of resistance, guerrilla warfare,” he said. “Then it led to a quagmire.”

James Monroe, whose portrait hangs in the Oval Office, issued his famous doctrine to warn Europe to stay out of American affairs.

Justino Vargas was a child (above), and Humberto Tafur (below) a young man, when they say they witnessed Operation Marquetalia. The attack in 1964 was ‘where the problems started,’ Mr. Tafur says.

By the time the planes were flying over, Mr. Tafur said, Colombia had committed fully three-quarters of its military to a counter-insurgency campaign in which the U.S. played an extensive role, at a moment when American political and military leadership was intently focused on ridding Latin America of Communist influence. The Colombian offensive was designed in part by U.S. planners, who dispatched special forces commanders to study the country’s military response capabilities, shipped in new hardware and advised Colombian army leaders on how to develop rapid response forces.

A U.S. Army mobile training team helped Colombian generals draft the plan that would lead to Operation Marquetalia, according to research published by the U.S. Army Special Operations History Office. It notes that Colombian authorities asked for help, and calls the broader U.S. involvement in the country “one of the most successful counter-insurgency campaigns of the time.” Colombians formed the largest group of soldiers trained by the U.S. at a warfare school in Panama. In Operation Marquetalia, Colombian forces used what are widely believed to be bombs provided by the U.S.

Eduardo Pizarro once led a commission set up to reconcile warring parties in Colombia’s long era of violence.

Yet what they sought to attack were largely men armed for “peasant self-defence. It was not guerrillas seeking to take power,” said Eduardo Pizarro, a political scientist who served as president of the National Reparation and Reconciliation Commission. But the U.S. has long kept a close eye on Colombia. “Since the ’60s, Colombia has, geopolitically, been a key country for Washington,” he said. “Because it is next to the Panama Canal, but also next to the Caribbean. So, if Colombia fell into the hands of the revolution, it could affect the stability of the Panama Canal and the entire Caribbean.” Mr. Pizarro, who has written extensively on the country’s internal conflicts, faults Colombia’s elites.

One of his brothers led the M-19 guerrilla group; another was killed by FARC, which nearly killed him, too. But the military response at Operation Marquetalia, he believes, was a mistake. Those in charge should have worked to “win the hearts and minds of the peasant population, to isolate the weak armed nuclei that were emerging,” he said. Instead, they decided “to annihilate the internal enemy.” Yet even when American intervention succeeded at winning those hearts and minds – the brief invasion of a small Caribbean country in 1983; or, perhaps, the surgical precision of Mr. Maduro’s seizure – that success has inspired future trouble.

St. George’s is the capital of Grenada, a Caribbean island that had a tumultuous first decade after winning independence from Britain in 1974. During strife between a socialist government and the military, U.S. forces invaded to shape the outcome.

U.S. forces arrested suspected Marxists on Oct. 30, 1983, while president Ronald Reagan backed a new interim government and defended his actions against criticism from the United Nations.

Historian Angus Martin visits the wall where, before U.S. forces arrived, the military junta executed prime minister Maurice Bishop. Mr. Martin says many Grenadians today think poorly of the invasion.

For two years and three months, Tillman Thomas lived behind bars in the prison high on a hill overlooking the harbour at the heart of Saint George’s, the capital of Grenada. He was among the hundreds of political prisoners held by the Cuba-friendly government of Maurice Bishop, who was executed in a hail of bullets on Oct. 19, 1983. Six days later, American paratroopers descended from the sky. Roughly 7,300 U.S. troops participated in Operation Urgent Fury, a full military invasion of a Commonwealth country ordered by Ronald Reagan. Grenada’s small military fought back with scattered anti-aircraft fire. A local radio station sought to inspire resistance by playing Jimmy Cliff’s Stand Up and Fight Back.

But Mr. Thomas, who would go on to become the country’s prime minister, was thrilled that the Americans had arrived. U.S. soldiers opened the cell to set him free. It was a moment, he said, when good triumphed over evil. “The people of Grenada were ready and happy with what took place,” he said. The Communist regime in power had destroyed itself and risked taking the country with it. The operation was so well-received that people on the island still debate whether to call it an invasion or an intervention; some have settled on “intervasion.” In its memory, Oct. 25 is still marked as a day of thanksgiving.

“It was totally successful,” said Jay Mandle, an economist at Colgate University who is author of Big Revolution, Small Country: The Rise and Fall of the Grenada Revolution. For the U.S., meanwhile, it constituted a major ideological victory against a Communist regime. American strength easily quashed revolutionary weakness, with consequences across the region. “What it did in the Caribbean was devastating to radical socialist nationalist politics,” said Prof. Mandle. In one decisive act, Mr. Reagan had reasserted U.S. dominance in the hemisphere. Grenada had turned to Cuba for help building its international airport; it was the U.S. that finished the job.

Had the U.S. not intervened, “we’d have been worse than Cuba,” said Mr. Bierzynski, the Grenada businessman. But in Grenada, “we got very lucky, and so did the Americans,” Mr. Bierzynski said. At that moment in history, “the strategic interests of Grenada and the United States of America happened to coincide.” Four decades later, that luck feels newly tenuous. Months before U.S. troops removed Mr. Maduro, the Trump administration asked to install a military radar at Grenada’s airport, which is located 150 kilometres from Venezuela. Local authorities balked at the request.

Then earlier this month, the U.S. raised its threat-level rating on Grenada, a potential blow to tourism. This week, Grenada was one of 75 countries from which the Trump administration said it would suspend immigrant visa processing. For Grenadians, views on 1983 have soured, too. Local historian Angus Martin estimates that a majority of the island now sees the invasion negatively. Young people, in particular, have begun to reconsider the progressive policies of past Marxist revolutionaries. But for the U.S., Grenada became a model to be replicated. “We were the one that made America feel that it could do all of this,” said Mr. Martin. “And then they did Panama.”

News of the Grenada operation came as a surprise to Ottawa and London, which voiced doubts about the invasion of a fellow Commonwealth country.

Andrew Bierzynski, a Grenadian businessman who helped U.S. forces in 1983, thinks little of Mr. Trump’s new ‘Donroe doctrine,’ calling it ‘the naked fist of American arrogance.’

Paula Rodríguez was three years old at the time of the Panama invasion, when her father died in defense of an airfield.

On the night her father died, Paula Rodríguez got herself in trouble for spilling Orange Crush on the white carpet in Manuel Noriega’s office. “That saved my life,” she said. Ms. Rodríguez was three at the time, and her father was a Panamanian air force lieutenant. That night, she was supposed to stay with him at the base where he served. Instead, she was sent home. Hours later, 24,000 U.S. troops moved to take control of the country under Operation Just Cause.

They installed a new government and, after Mr. Noriega surrendered, removed him from Panama. In a speech on Dec. 20, 1989, then-president George H.W. Bush said he had acted to protect Americans living in the country, but also to combat drug trafficking and “protect the integrity of the Panama Canal Treaty.” By then, Ms. Rodríguez’s father was dead. He led a platoon to defend the airfield. They set an ambush for the U.S. troops, killing several of them. Mr. Rodríguez was killed, too.

Mr. Noriega’s whereabouts were still unknown the morning after the invasion: He would not surrender until Jan. 3, 1990.

Like in Grenada, the invasion was popular at the time. Overwhelming numbers of Panamanians initially said they supported the removal of Mr. Noriega, a military dictator who had annulled one election and stolen another. Today, many wonder why it had to be so violent. In El Chorrillo, the neighborhood where Mr. Noriega had his headquarters, the walls of a sports facility built on the site of his former compound are decorated with large text: “I do not forget. Nor do I forgive.” On murals, American soldiers are depicted with skulls for faces.

Parts of the neighborhood were razed in the attack, which burned wooden apartment buildings to the ground. Alberto Adal remembers the sounds of the helicopters flying low over the rooftops, the soldiers who emerged with faces painted, the rifles. “There were dead people all over the place,” he said. Mr. Noriega had regularly strolled the neighborhood, providing Christmas trees for its residents, recalls Enrique Torre, who is now 73. He still struggles to understand why the invasion took place. “The Americans could have just arrested him,” he said.

Enrique Torre and Alberto Adal, now in their 70s, remember the devastation in El Chorillo when the U.S. forces came.

But experience of the invasion has given Panamanians cause to think deeply about the U.S., whose interests in the narrow waist of Central America predate the establishment of Panama as a country. There should be no surprise that an American president is willing to orchestrate a foreign military intervention, said Danilo Toro, a Panamanian sociologist. Each president in the postwar era has done so, no matter their political leaning. In a way, he said, countries that feel they are next can be grateful to Mr. Trump, who he calls “the most predictable president I’ve ever studied.” The President has made clear his intentions, in major speeches like the one at his inauguration and in his vast volumes of public discourse.

Besides, Prof. Toro said, “there’s more coherence in Trump’s international policy than most other presidents.” Where other U.S. leaders have found themselves torn between economic priorities and national-security imperatives, for Mr. Trump, “both things are the same.” Seizing Mr. Maduro removed from power an ally of Iran and Russia, while giving the U.S. access to oil and critical minerals. In Panama lies a similar confluence of interests. The U.S., he said, is best seen as a successor to the Persians, the Romans and the Ming. “Great powers have a vision of wanting control,” he said. For Panama, that idea continues to stir feelings of vulnerability, even as some continue to hold up their past, and their pain, as a warning. For Ms. Rodríguez, time has done little to lighten the burden of growing up without a father.

Three years ago, she went to a Panamanian air force base, convinced the U.S. was preparing for another invasion. “That made me lose it, the fear of being attacked again,” she said. She was taken to a mental institution, where she spent two months heavily medicated. She emerged with a renewed ambition to advocate for reconciliation with a past that is, for her, as personal as it is political. The country has yet to complete a full list of those killed in the invasion. Nor has it erected a monument to the fallen. Families continue to demand compensation, too. Those working to remember include Ms. Rodríguez’s mother, Trinidad Ayola, who leads an association that advocates for those who lost relatives and friends in 1989. For Ms. Ayola, watching the attack on Caracas earlier this month rekindled stresses she felt in 1989.

Panamanian sociologist Danilo Toro considers Mr. Trump the ‘most predictable president I’ve ever studied’ in matters of foreign policy.

The invasion of Panama yielded little in obvious gains for the U.S. A decade later, it pulled out of its military bases in the country and transferred the canal into Panamanian hands. “They didn’t get anything,” Ms. Ayola said. Now, she worries that, at a time of the Donroe Doctrine, this constitutes unfinished business for the White House. Either way, she said, Panama offers a lesson to a hemisphere contemplating how to prepare for what lies ahead, a time with little room for sentimentality. “Do not trust the Americans,” she said. The U.S. “just looks out for its own interests. They are not friends with anybody.”

Our Thanks to the Toronto Globe and Mail Newspaper for this article sent to us by Malcolm in Panama.