The Railroad that Helped Chiriquí Grow Reappears on a Map

A citizen initiative rescues the route of the train that boosted the development of Chiriquí in the first half of the 20th century. The map can be consulted at the Ernesto J. Castillero National Library.

The railway history of Chiriquí is taking shape again thanks to a citizen effort that managed to recover and map, for the first time, the actual route of the old railway. This is a cultural and historical project that rescues a key piece of the development of Chiriquí, now converted into an official document and heritage for public consultation in the National Library of Panama. The initiative began in the midst of the pandemic, when a group of citizens created a Facebook group to share memories, facts, and discoveries about the train.

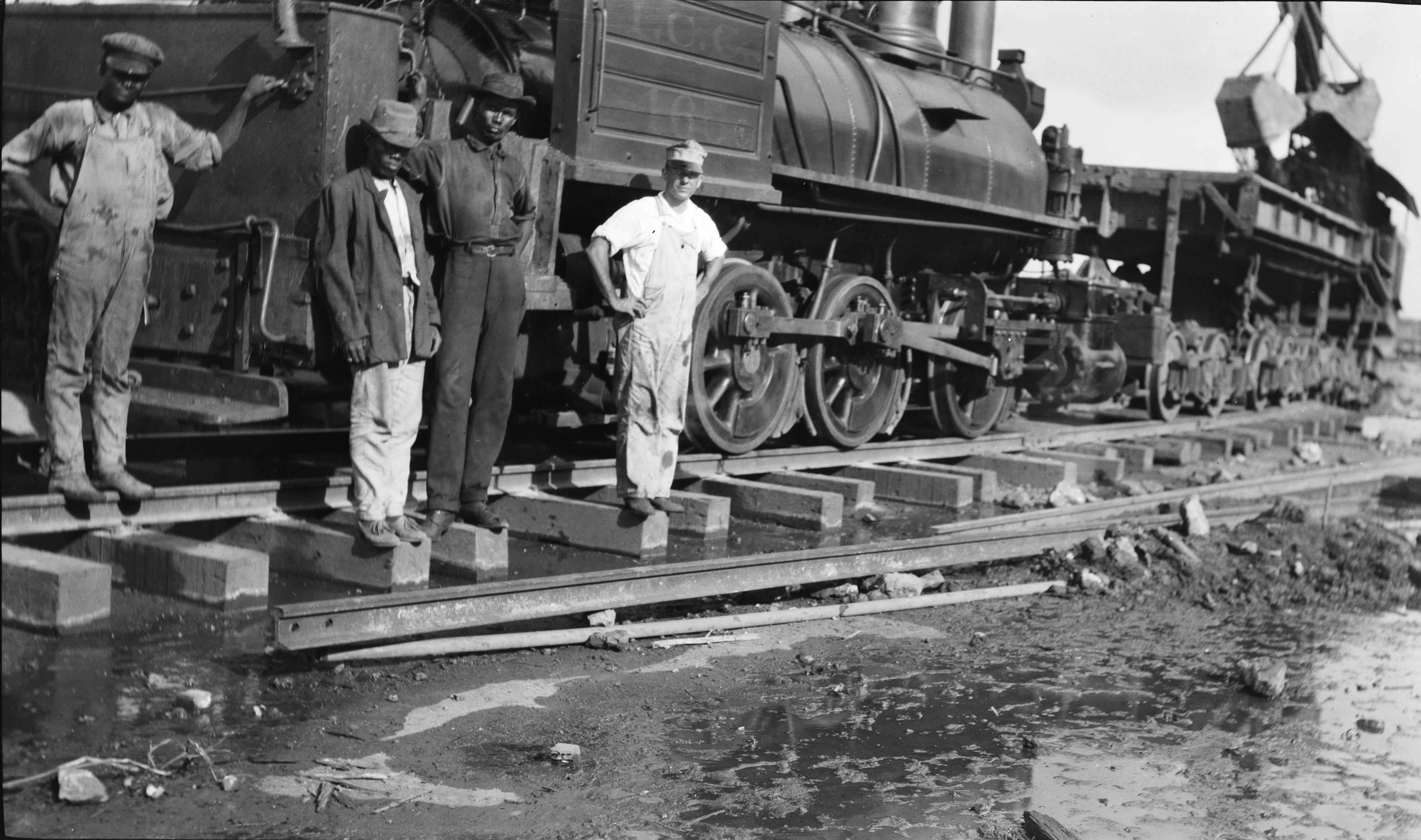

Over time, this virtual meeting place transformed into the Friends for the Rescue of the Chiriquí Railroad movement, bringing together engineers, historians, teachers, artists, and communicators. According to Sergio Anguina, spokesperson for the group, the project is considered historic because the railroad was the first motorized transportation system to connect towns, agricultural areas, and ports in the province.

“From 1916 and for much of the 20th century, it defined routes, boosted the development of entire towns, and shaped the layout of roads that still follow its original path today.” One of the map’s greatest contributions, he explained, is clarifying historical gaps, since Chiriquí didn’t have just one railway system, but two: the national system, also used for passenger transport, and the United Fruit Company’s system, dedicated to banana production and even connected to Costa Rica.

This difference had never before been depicted on a single map. According to Anguina, reconstructing the railway map took nearly two years and involved fieldwork, reviewing military maps from the 1950s and 60s, geo-referencing, and using digital tools such as Google Earth and ArcGIS. The result was a technical collage that integrates all the scattered information into a single official document.

The Results

Although the rails disappeared, field research revealed that the last ones were removed in the early 2000s. “The remains of the railroad were not completely lost. Bridges, drainage systems, and other structures still survive, and many rails were reused as fence posts, columns, bull bars on rural roads, and even utility pole supports,” he noted. The map, now housed in the National Library, helps us understand how communities like David, Bugaba, and Puerto Armuelles grew up around the train.

“For decades, the Chiriquí Railroad was the most economical and accessible means of transportation for thousands of people. It connected rural communities with urban centers, allowing the movement of workers, students, and producers who depended on this system for their daily lives,” he pointed out. Today, the restoration of its route serves as a reminder of the importance of valuing the works of the past. The map not only recovers a lost infrastructure, but also encourages the protection of Chiriquí’s material history as an essential part of its cultural and social identity, he indicated.