‘Just Cause’ the US Invasion of Panama December 20 of 1989: Tours and Immersive Rooms Mark the Commemorative Day

The participating organizations highlighted the importance of culture and education as fundamental tools for preserving historical memory and strengthening national identity.

This weekend, the Panama Canal Museum opened its doors free of charge to the public, in a day that brought together both Panamanians and foreign visitors. The initiative was carried out within the framework of the National Day of Mourning and was part of a special agenda of cultural and educational activities to commemorate the 36th anniversary of the United States military invasion of Panama. The program was designed to promote reflection and collective memory, pay tribute to the victims, and highlight the stories of the communities affected by the events of December 20, 1989.

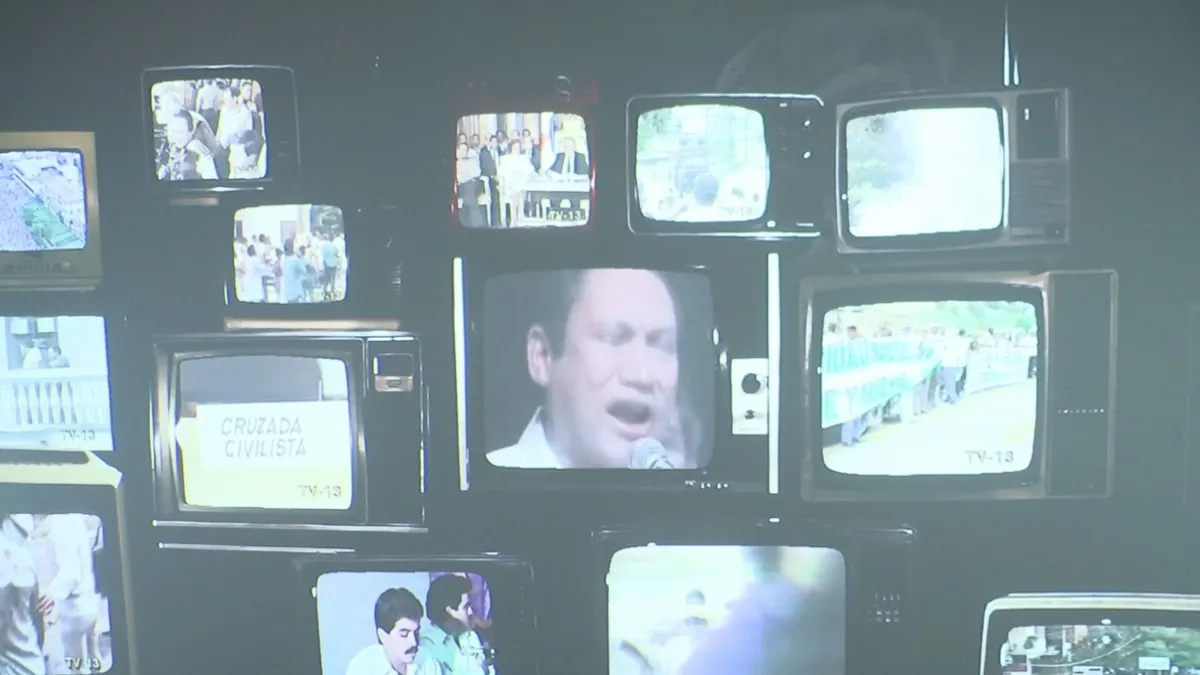

The president of the Panama Canal Museum, Hidelgar Vásquez, explained that this exhibition is held every year as part of the institution’s responsibility to recognize the historical importance of this event. She also emphasized that it is the only exhibition of its kind in the country. “The entire museum team makes sure that these open days can take place and that both Panamanians and foreigners can perceive what that moment in our history was like,” he said. During December 20th, guided tours, screenings and workshops were held, with the participation of communities from Santa Ana and El Chorrillo, integrating territory, memory and urban history.

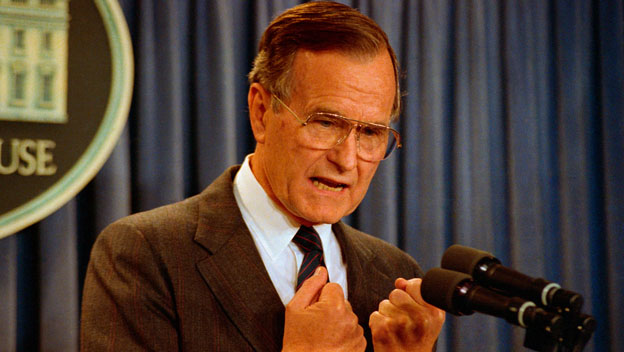

Pictured above is former US President George Bush Senior broadcasting the orders to take out Noriega.

Temi Núñez, a museum guide, explained that the space features an immersive room with excerpts and narratives from family members who lost loved ones, as well as a reenactment of how the invasion unfolded. She added that many tourists show interest and often ask about the causes of the events. Throughout the day, the museum welcomed numerous national and international visitors interested in learning more about the history of December 20th and the construction of the Panama Canal. Several expressed satisfaction with the tour and noted that they learned new information. The participating organizations highlighted the importance of culture and education as fundamental tools for preserving historical memory and strengthening national identity.

Rubén Blades Questions Why the True Number of Victims in the Invasion ‘Just Cause’ is Still Unknown

On this National Day of Mourning, the Panamanian singer-songwriter said that “despite the magnitude of ‘Just Cause’, the incident has still not been properly studied, analyzed, and resolved.” There isn’t even certainty about how many of our compatriots died.”

Panama mourns the victims of the 1989 military invasion, an event that profoundly marked our country and many Panamanian families. Today we remember those who lost their lives, honor their memory, and reflect on the importance of sovereignty, peace, and respect for life, so that history is not forgotten and remains alive in the national consciousness.

Noriega’s Final Hours According to News Reporting at the Time

Manuel Antonio Noriega sought refuge in the Apostolic Nunciature of Panama on December 24, 1989, four days after the start of the U.S. invasion. He did not leave until January 3, 1990. The Apostolic Nuncio to Panama, José Sebastián Laboa, was on vacation in his hometown of San Sebastián, Spain, when he learned that Panama had been invaded. It was December 20, 1989, and the news was delivered to him by Joseph Spiteri, the secretary of the Nunciature. Without much hesitation, Laboa went to the airport and flew to Madrid. From there he traveled to Miami, Florida, where a group of Panamanian exiles arranged a flight for him to Panama.

Omar Torrijos Manuel Antonio Noriega Ernesto Perez Balladares

On December 22, two days after the start of the U.S. invasion of Panama, Laboa landed at a military base in the Canal Zone, and from there he was taken to the Papal Nunciature on Balboa Avenue. When he arrived at the diplomatic building, Laboa found it packed: military personnel and officials, and even a group of ETA members who had run towards the Vatican embassy to ask for refuge, and they occupied every space and every corner of the lower floor of the structure. While Laboa took control of the situation, the city suffered the relentless disorder of anarchy.

Uncertain Times

For a year, the government had been paying with promissory notes, and families did what they could to have rice, beans, and prickly pear on the table. “You tried to have the essentials; it wasn’t like you had a pantry stocked for three months,” Ramón Flores recalls, about that year, 1989. It was December, and the Panamanian government was in turmoil. From president to president—installed and removed by Manuel Antonio Noriega—the population sensed an impending invasion and tried to take precautions. On Sunday, December 3, the newspapers announced how the second half of November and the first two weeks of December would be paid.

Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega at a ceremony commemorating the death of the national hero, Omar Torrijos, in Panama City.

“Public employees will have a happy Christmas,” the government promised. Day after day, the newspapers reported what was happening: “Upstart troops storm water treatment plant.” “U.S. army blocks entrance to Cerro Patacón.” “People’s outcry: General Noriega, head of government.” Around that time, in El Chorrillo, where the Modelo prison and the Central Barracks were located, a shooting range with obstacle courses was inaugurated in the area known as “El Límite,” where the Defense Forces planned to “train the patriotic generation of the year 2000.” On December 16, Manuel Antonio Noriega finally achieved what he wanted: “Noriega is declared head of government by the National Assembly of Representatives,” Crítica reported. “As head of government, Noriega acquires extraordinary powers that ensure he can achieve the objectives of the national liberation struggle.”

‘We feel fear, a lot of fear’

With his own handwriting, Father Javier Arteta began writing at midnight on the 19th to the 20th. He was in the Fatima parish building, on 26th Street West in El Chorrillo, and amidst the chaos he recounted: “An intense shootout began, gunshots, explosions, three helicopters circling the area. We woke up, and all of El Chorrillo woke up startled. We all understood that this wasn’t a normal shootout, but something truly serious. Most of us felt fear. A lot of fear.” When María Flores found out what was happening, she picked up the phone and called her brother Ramón: “The invasion has begun. The gringos have invaded us,” she said into the phone in a whisper, as if she didn’t want anyone in the world to hear her. Then, all the walls of Ramón’s house began to shake. Nearby was the Tinajitas Barracks, and in the dark sky, airplanes could be heard roaring.

Seconds later came the sound: Boom! And the glass ornaments rattled. Boom! Boom! And the windowpanes began to shake. The United States was in the midst of its “Just Cause” and on the street where Ramón lived there was a fearful silence. “It was a long night,” Arteta wrote from El Chorrillo. “People kept coming and coming. Loud gunshots could be heard… There were moments of panic and hysteria. We began to pray a Hail Mary. We believe it was the largest and most fervently prayed Hail Mary in the entire history of our parish.” Four days later, on December 24 , the entire city was still a madhouse. Without police, military, or law enforcement, part of the population resorted to theft. “They steal everything, they steal,” Arteta wrote. At 5:30 p.m. that same day, the religious community of Fatima heard on the radio that Noriega had taken refuge in the Apostolic Nunciature. “We were driving along Pedregal and almost went off the road.”

Christmas Delivery

It was 9:30 a.m. when Nuncio Laboa received a call: “Okay, okay. Immediately.” He turned to César Tribaldos, leader of the Civic Crusade, who was having breakfast with him at that moment. “Put on a priest’s shirt,” he told him. Tribaldos had become friends with the Nuncio, after the various refuges he had enjoyed at the Embassy of the Vatican State, from 1987 to 1989. Without knowing why, and not entirely sure that any priest’s shirt would fit him, Tribaldos was trying to figure out “how to squeeze into the shirt” when the phone rang again. It was Mario Rognoni, a member of the Democratic Revolutionary Party and a close friend of Noriega. “Mario? Maíto?” Tribaldos said. “Yes, this is Tribi.” After the customary greeting, Rognoni asked Laboa: “Yes, yes, well… No; it’s fine. I’ll see what I can do.”

Then Laboa asked Tribaldos to take off his shirt and went to Father Javier Villanueva, who from his pulpit in the Cristo Rey Church had strongly denounced the military regime. “Would you go looking for Noriega?” he asked. Minutes later, Villanueva was on his way to a Dairy Queen near the racetrack in Juan Díaz, accompanied by Spiteri. They had to wait about 20 minutes before a blue van with a sliding side door appeared. When it opened, Noriega emerged. He was wearing a military green sweater, Bermuda shorts, and Jumbo brand flip-flops. Father Villanueva looked at him and said, “You know me? Well, come on in.” Noriega slid from the van into the Nunciature car – which had a Vatican flag – and the bodyguard, who was driving the van, dared to ask him: “Boss, what about me?” Noriega took only seconds: “You? Get lost!”

A Small, Big-Headed Man

The first thing Noriega did when he arrived at the Nunciature was order a very cold beer. It was lunchtime, and Laboa led him to the guest room upstairs, where Tribaldos and former president Guillermo Endara, among others, had previously stayed. From the Nunciature, Lahoa informed Foreign Minister Julio Linares that Noriega was there seeking asylum, and minutes later the entire Balboa Avenue began to tremble: US Army tanks were rolling down the seawall, while helicopters flew over the roof of the Nunciature. “That was a roar, a roar… Because there were many tanks coming down Balboa Avenue; from all sides, and six helicopters that hovered over the Nunciature,” Tribaldos explains. Enrique Jelensky arrived the next day, on December 25.

Also a friend of Laboa, he offered to be the “interpreter” between the American soldiers and Laboa, who did not speak much English. “The atmosphere was tense,” Jelensky recalls. With so many people, the amount of food consumed at the Nunciature was enormous, and Jelensky was in charge of going out almost daily to do the shopping at a nearby supermarket. Since the entire country already knew that Noriega was there in exile, every time the gates of the Nunciature opened, the shouting, insults, and demands would begin. “When I came out, people would yell all sorts of things at me,” Jelenzky recalls. “If he didn’t have the curtains closed, he would see an American soldier pointing a gun at him,” Jelensky explains. Tribaldos didn’t see Noriega until two days after his arrival.

As he was a regular visitor to the embassy, the nuncio Laboa had given him keys so he could enter without knocking, and he also had a “credential” that allowed him to pass among the tanks and soldiers without problems. It was December 26th, and Tribaldos passed through the iron gate and reached the main door of the Nunciature. As the key turned and he pushed open the door to enter, he felt something blocking him from the inside. “What’s happening? What’s happening?!” he shouted, and pushed harder. Then Asunción Eliécer Gaytán, Noriega’s loyal companion, appeared: “No, no…excuse me, Don César.”

When he entered, Tribaldos and Noriega looked at each other. “As soon as he saw me, his eyes widened and he ran out. He took the stairs two at a time.” Noriega was wearing the same green sweater, the same shorts, and the same Jumbo store flip-flops. At that moment, Tribaldos realized that, without a uniform or military protection, Noriega was actually a small, thin, big-headed man. “A head that is a little disproportionate to the size of his body,” the former Crusade leader noted.

In the Sniper’s Crosshairs

American soldiers guard the vicinity of the Apostolic Nunciature of Panama after Manuel Antonio Noriega sought asylum at that diplomatic headquarters following the invasion of December 1989.

Jelensky says that Noriega never slept with the door closed and that the curtains of the only window in the room where he slept, were always drawn. That one night, after they had gone to bed, the ground shook and there was a loud crash. Noriega and Jelensky jumped out of bed. “I slept in the room next to Noriega’s,” Jelensky explained. Frightened, Noriega asked Jelensky to come downstairs to find out what was happening. “It was the first time he had ever spoken to me.” When he went downstairs, he realized: on a plot of land facing Via Italia, on one side of the Nunciature, the Americans had decided to flatten the ground with bulldozers so that helicopters could land. “This made the building shake,” Jelensky explained.

|

On the other side of the Nunciature there was a building with several levels of parking, and the room where Noriega slept faced those parking lots. On one of those levels, right above the bedroom designated for the “strongman,” an American had been stationed. He was there, day and night, at all hours, with a gun. “If he didn’t have the curtains closed, he’d see an American soldier pointing a gun at him,” he said. While Noriega, other military personnel, and officials remained sheltered in the Nunciature, in El Chorrillo they were still mourning the destruction wrought by fire on the first day of the invasion.

“Has anyone seen the face of an entire family that has just lost its home and is left with only the clothes on its back, hugging each other tightly, feeling each other to make sure everyone is alive?” In the neighborhood, reduced to ashes, the Mercedarian friars had also had to burn some corpses. “Around mid-morning we burned another body that was inside a cart and crushed. Crows were eating it. The soldiers almost wouldn’t let us. The dead man was a Panamanian guard, and when the cart burned, a number of bullets were fired, startling the nearby tanks.” Several days later, Arteta wrote in his diary: “We burned two more bodies. That makes six.”

The End of Ceausescu

Images arrived at the Apostolic Nunciature from Romania. Nicolae Ceausescu appeared in a small room, accompanied by his wife Elena, as a military tribunal tried them for their actions. Ceausescu had ruled Romania dictatorially for 20 years, and his time had come. Minutes later, in images that circulated around the world, the couple appeared lying on the floor, shot, entangled in their own blood. “One day,” Tribaldos recounts, “a member of the PRD, a party leader, came out and spoke ill of Noriega. He was someone I trusted, and I felt betrayed.” Then came the Ceausescu affair and the “great march” that the civilian leaders had been announcing. “This march was organized on Balboa Avenue, and there was a huge crowd,” the leader recalls.

After several days inside the Nunciature, the civilians had decided to demonstrate to demand Noriega’s surrender and filled the old boardwalk. ‘I think that’s when he realized he could go on to a worse life if he didn’t turn himself in,’ Tribaldos reflected. On the night of January 3, 1990, CNN journalists stationed near the old Holiday Inn in Paitilla called Tribaldos: “Look, there’s a man in uniform leaving the Nunciature who looks like Noriega. Can you confirm this?” Tribaldos, who lived nearby, ran down to where the journalists were and watched the video: “That’s Noriega,” he told them. And then Noriega was seen dressed in his military uniform, downcast and submissive, surrendering to the United States Army.