Experts Stunned After Noticing Dramatic Change in the Gulf of Panama Earlier This Year: ‘We’ve Never Seen This Happen’

This has serious implications. For the first time in decades, the Gulf of Panama’s seasonal upwelling — an otherwise predictable phenomenon — has collapsed, Geographical reported.

How Waters in the Gulf of Panama are Changing

Scalloped hammerheads gather in the region feasting on the profusion of small fish

For the first time on record, the cold, nutrient- rich waters that sustain an entire ecosystem failed to surface in the Gulf of Panama. Every year, a plume of cold water rises to the surface in the Gulf of Panama, bringing with it a colossal surge of life – from phytoplankton to migratory sharks and whales. Except that this year, it didn’t. When Aaron O’Dea, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, reported his team’s findings earlier this year, media headlines announced that Panama’s ocean upwelling had failed for the first time in 40 years. ‘What we actually said was that we only have 40 years’ worth of high-quality data and that, within those 40 years, we’ve never seen this happen,’ says O’Dea. In reality, scientists don’t know whether anything like this has happened before, or whether it will happen again.

‘We did go back and change the press release,’ O’Dea adds, ‘but by then it was too late.’ Ocean upwelling is a process where deeper, colder and nutrient- rich water rises to replace warmer, nutrient-depleted and less dense surface water that has been pushed away by prevailing winds. In the Gulf of Panama, it has been a remarkably predictable phenomenon – at least for the last 40 years that scientists have been monitoring it – always beginning by 20 January, lasting around 66 days, and dropping the surface temperature to 19°C or above. O’Dea explains that this predictability is a direct result of the Earth’s orbital tilt, which causes an annual shift in the planet’s most intensely heated zone (the area where the sun shines most directly), creating the wandering band of low pressure known as the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

As hot air rises within the ITCZ, it generates a massive, dependable system of atmospheric circulation – the Hadley Cells – which in turn powers the trade winds that have been essential to global navigation since the age of sail, and which reliably drives the ocean upwelling in the Gulf of Panama. We also know that this process has occurred in one form or another, for a very long time. The ecosystems that rely on this surge of available food have existed for hundreds of thousands of years. Scientists who have analyzed the isotopic compositions (chemical signatures that reflect temperature and salinity changes in the water) of two- to three-million-year-old shells from the Gulf of Panama have also found that they contain clear seasonal patterns, much like shells today.

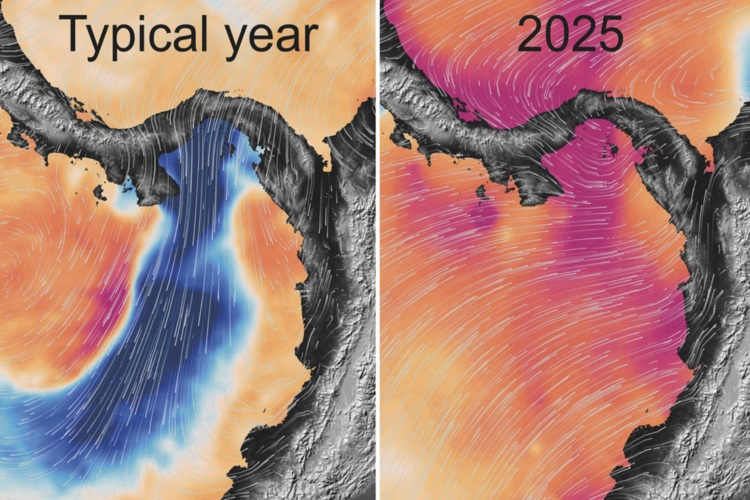

Left, water temperature in a typical year; right temperatures this year

‘In the tropics, where year-round temperatures are usually stable [unlike the strong seasonality at high latitudes], such seasonal cycles are only caused by upwelling,’ says O’Dea. ‘It’s unequivocal evidence going back about three million years.’ This year, temperatures in the Gulf of Panama didn’t start to change until 4 March. The drop, which only reached 23.3°C, lasted just 12 days. O’Dea and his colleagues are fairly confident that less frequent (they reported a 74 per cent decrease) and shorter-lasting northerly winds caused the upwelling to fail, and suspect that these winds were the result of La Niña conditions. Without further research into both past and future events, they won’t be able to know whether this was an isolated incident or the start of a new trend.

So far, anecdotal evidence suggests that this year’s conditions in the Gulf of Panama have had an impact on small pelagic fish – such as anchovy and herring, which are food for larger fish such as tuna – whose populations are strongly correlated to the strength of the upwelling. ‘These are fish that reproduce very quickly, grow very quickly and die very young,’ says O’Dea. ‘The turnover is really fast, so you see the effect immediately. And we’re hearing that the catch for this year has already dropped quite significantly.’ O’Dea hopes to extend existing records of Panama’s ocean upwelling beyond the last 40 years by looking at lower-quality (less reliable) older data and new climate models that can help reconstruct the past. He also plans to begin monitoring again in January, when the 2026 upwelling is due to start – a task that, due to the lack of researchers and funding in the region, could prove even more difficult.

What’s Happening?

Every year, upwelling brings cold, nutrient-rich waters from the ocean’s depths to the surface, replacing the warmer, nutrient-depleted water. This typically occurs during January to April, when the Intertropical Convergence Zone shifts south and generates northerly trade winds. But this year, the upwelling failed, and researchers don’t yet know whether it was a one-off or a new trend. “What we actually said was that we only have 40 years’ worth of high-quality data and that, within those 40 years, we’ve never seen this happen,” said Aaron O’Dea, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, per Geographical. STRI scientists Andrew Sellers and O’Dea shared that this natural process sustains fisheries and helps protect coral reefs from thermal stress, which could worsen their bleaching.

Why is Panama’s Ocean Upwelling Important?

A weakened upwelling threatens coastal communities that depend on stable fisheries for income and food security, placing additional pressure on local systems. Based on anecdotal evidence, the failed upwelling has already affected small pelagic fish, like anchovies and herring, according to the Geographical report. In a paper published in PNAS, STRI researchers found that this “unprecedented suppression” of the upwelling was linked to “anomalous wind patterns” that could, in turn, have been affected by La Niña conditions. This Pacific upwelling is important for marine communities, modern fisheries, and even pre-Columbian societies that rely on it.

It fuels the production of phytoplankton, which form the foundation of aquatic food webs and produce approximately half of the Earth’s oxygen, explained the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. This failed upwelling could affect the productivity of fisheries and, in turn, impact food webs and fishing industries. This could stress food webs, making them more vulnerable to invasive species that compete with native plants and animals for already limited resources.

When invasive species take advantage of weakened ecosystems, they quickly out-compete native species for food and habitat, threatening local fisheries and food supply. According to a press release from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, climate disruption can have a significant impact on these oceanic processes. Meanwhile, rising global temperatures are fueling not just extreme weather events but also changes in ocean temperatures and phytoplankton populations.

What’s Being Done About This Changing Phenomenon?

The STRI researchers plan to start monitoring Panama’s ocean in January 2026, when the upwelling is expected to begin, to help them assess the impact of such disruptions on marine ecosystems. However, the lack of funding and researchers can make this more challenging. Individuals can help by understanding and discussing broader climate issues, like what’s happening in the Gulf of Panama, to spark meaningful conversations and enable others to make smarter decisions for a better future. Similar conservation efforts in other regions show how long-term monitoring and habitat protection can help communities respond to environmental disruptions.

In a Reddit post sharing similar news covered by another outlet, users shared their thoughts on how this phenomenon could affect humans and marine ecosystems. “One can only imagine all the knock-on effects that such a catastrophe causes, both locally and overall. I imagine this could well devastate both human and pelagic ecologies, and hasten the process elsewhere,” a Redditor wrote. “This has serious implications for marine ecosystems and food security. And it’s not just Panama. Tropical upwelling zones globally are collapsing yet poorly monitored,” echoed one user.