Panama and Canada lead a Push for Less Shipping Noise on the Ocean

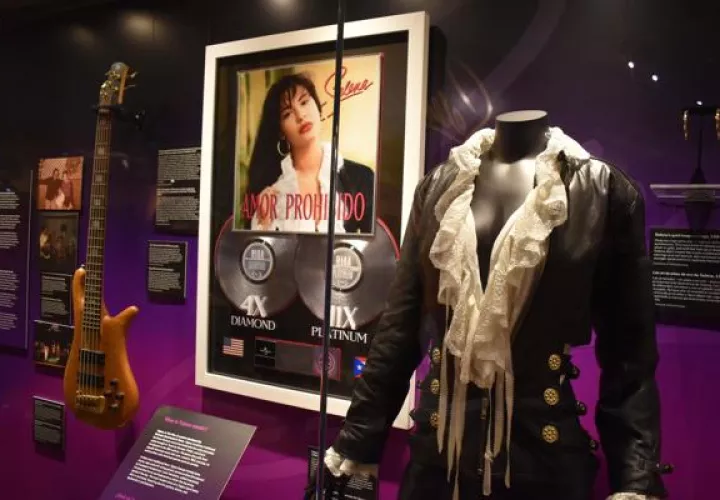

Bulk carrier Hauke Oldendorff heads to Milne Port to retrieve a load of iron ore from Mary River Mine on Baffin Island, Nunavut. Marine animals are negatively affected by underwater noise – especially noise from ships

A coalition for a quiet ocean, launched at the third United Nations Ocean Conference this week, aims to curb noise pollution caused by the global shipping industry to protect marine life. The declaration, which is co-led by Canada and Panama, was signed by the 27 member countries of the European Union, as well as Belize, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay. The members of the coalition collectively represent more than 50 per cent of the globally flagged fleet, and “they are committed to ambitious and practical solutions that will reduce the impacts of underwater noise,” said Stéphane Dion, Canada’s ambassador to France and Monaco, speaking at the launch of the High Ambition Coalition for a Quiet Ocean in Nice, France, on behalf of federal Transport Minister Chrystia Freeland.

The commitment to reduce the impact of underwater noise is crucial for protecting marine biodiversity, said Mr. Dion. More than 130 marine species globally, from large marine mammals to small invertebrates, are negatively affected by underwater noise – especially noise from ships, which are by far the heaviest users of the ocean, he said. “In such a noisy ocean, species cannot communicate, they cannot navigate, they cannot find food, and they cannot care for their young. It is not sustainable.” How have Canada and the U.S. tried to save North Atlantic right whales? Alexander James Ootoowak, an Inuk hunter and diesel mechanic from Pond Inlet, Nunavut, has witnessed that problem play out with narwhals, the tusked Arctic whales that Inuit rely on as an essential food source.

Speaking to The Globe and Mail from Nunavut, Mr. Ootoowak recalled a spring day hunting off the coast of his northern Baffin Island community at the eastern entrance of the Northwest Passage when a passing icebreaker escorting a fuel supply ship spooked a pod of narwhals. “The narwhal had gotten completely quiet, and they disappeared, it seemed like, until the ships passed,” says Mr. Ootoowak, who was hunting with his cousin. Having re-launched their 16-foot boat from the ice pan where the men waited for the narwhals to pass, the whales unexpectedly resurfaced. “They could not hear us drive up to them. I’ve never had that instance in my life where a narwhal is unable to hear an oncoming boat. It was just deafened by the icebreaker that was passing by,” says Mr. Ootoowak.

Narwhals rely on sound, specifically echolocation, to communicate, hunt and navigate. Shifts in habitat make North Atlantic right whales harder to track – and to save from extinction. In direct response to Inuit accounts like Mr. Ootoowak’s, the Mary River Mine, an iron ore mine on Baffin Island operated by Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation, took measures to mitigate shipping noise pollution. “We delay the start of the shipping season until icebreaking is no longer required for ore carriers sailing toward Milne Port, in an effort to reduce potential cumulative impacts to narwhal during this sensitive period of time,” reports the company’s website, which details other measures, such as deploying convoys, in which vessels travel as a group to minimize underwater sound exposure.

Mr. Ootoowak hopes the quiet ocean declaration will help make such best practices more common, while also shining a light on what Inuit have long known to be true. “If you talk to the Elders and Inuit here, it’s been a known fact,” he says of the relationship between noise pollution and narwhal behavior. Last year, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada reported that while narwhal abundance in the country is healthy, climate change, which is speeding up summer sea ice retreat and opening the Arctic to increased vessel traffic and noise, poses risks to the species. “I’m happy that something is being done about it,” says Mr. Ootoowak of this week’s announcement. “UN treaty to protect high seas gains global support, but falls short of ratification”.

Mary Tobin Oates, a senior policy adviser for the Inuit Circumpolar Council of Canada, says interviews with Inuit hunters as early as 1980 show that underwater noise from ships is deleterious to sea mammals. “It’s now 2025. We have 45 years of experience of underwater radiated noise. So, people, industry, organizations, states, should listen to our experience and accept it as fact, not just because the science supports it, but because Inuit support it,” said Ms. Tobin Oates, speaking in Nice. Kristin Westdal, a marine biologist and science director at the non-profit Oceans North, says the best way to understand what a healthy quiet ocean sounds like is “by listening to and working with the people who live here and have been monitoring their waters for generations.”

That effort is underway, says Dr. Westdal, “We look forward to working with Canada alongside Indigenous organizations and communities.” The quiet ocean declaration, which is open to all countries, outlines voluntary actions that governments and the shipping industry can take – such as advancing new policies to quiet ships, incorporating acoustic protection into marine protected areas, implementing vessel-based noise mitigation measures, and supporting international capacity-building – to restore a quieter ocean. This work also recognizes that shipping is critical to the economies of coastal communities, says Michelle Sanders, the alternate permanent representative of Canada to the International Maritime Organization.

“Shipping has a really important role to play, but we need to make sure that it is sustainable, so that we can continue to have the trade and the access to goods that is so critical for coastal economies,” said Ms. Sanders speaking in Nice. “If people live up to their words, live up to the high ambition coalition, it would be great. We would have less noise in the Arctic and the oceans generally. But I’m mostly concerned about the Arctic Ocean, because that is where the Inuit live and where they hunt, they fish, they thrive,” says Ms. Tobin Oates. From summer to fall in Pond Inlet, Baffinland charters up to 80 ore carriers – from bulk carriers to supply ships – to service the mine, according to its website. Add to that as many as 30 cruise ships come into town, says Mr. Ootoowak. “To put it into perspective, there’s rarely a day you look out your window and not see a ship going in either direction, in front of Pond Inlet,” he says.

Story from Jenn Thornhill Verma, from Nice France