Pablo Escobar’s Sinister Legacy in Colombia: Minors Hired to Kill

They returned to the nation’s memory this week, following the attempted assassination of presidential candidate Miguel Uribe while he was meeting with supporters in a Bogotá park on Saturday.

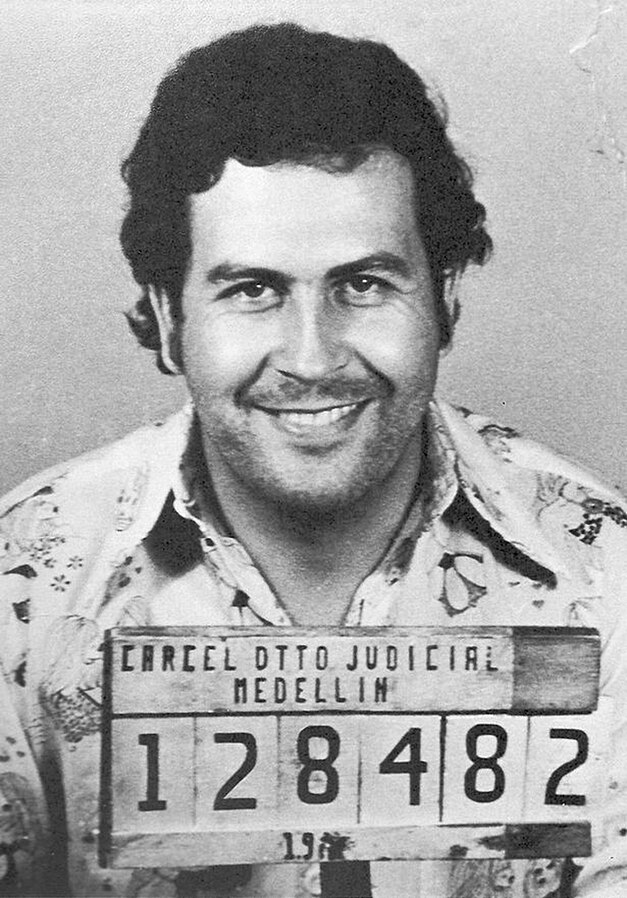

Bogotá, Colombia: During the 1980s, Pablo Escobar formed an army of poor teenagers determined to kill police officers, politicians, and judges. With drug money, he convinced them to commit horrific crimes, a legacy that lives on in Colombia. These types of crimes, common during the time of the drug lord who was killed in 1993, returned to the country’s memory this week, following the attempted assassination of presidential candidate Miguel Uribe while he was meeting with supporters in a Bogotá park on Saturday. On Tuesday, June 10, prosecutors charged a 15-year-old boy with allegedly shooting the 39-year-old political leader, who is in critical condition at a clinic. The young man pleaded not guilty and is in custody.

A video shows the alleged attacker moving through the crowd wearing a printed T-shirt and jeans. At one point, he pulls out a gun and aims it. Shots ring out, Uribe falls, and the crowd disperses in panic. The prosecution claims that he shot him three times. This “is not something unusual for Colombia,” says Mathew Charles, former UNICEF advisor in Colombia and director of the Mi Historia foundation for the inclusion of vulnerable youth. Colombian Attorney General Luz Adriana Camargo said Monday that criminal gangs use minors because the legal framework for criminals differs from that for adults and provides for lighter sentences. In 2024 alone, nearly 5,000 adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17 entered the Colombian criminal justice system after committing crimes, including homicide, according to the Ministry of Justice. Young people who take up guns often come from marginalized neighborhoods, with little access to education and fragile family backgrounds, says Charles.

With the lack of opportunities, crime seems like the only way out. “They’re looking for quick solutions to get money because there’s no food on the table at night at home,” he explains. Thirty-three percent of Colombians are poor. Nearly 4% of school-aged children and adolescents dropped out of school in 2023, the year of the last official report. Illegal groups pay minors between $50 and $500 per kill, according to Charles’s investigations. They are often “deceived” and never see the promised money, he says. When he was arrested, the minor accused of shooting Uribe said he was willing to “cooperate” with authorities and that he had received orders from someone in the “olla,” as drug dealing points are known in Colombia. Astrid Cáceres, director of the state agency responsible for the protection of minors (ICBF) , says that in many cases, mafias “provoke” minors to commit crimes “through the consumption” of psychoactive substances.

Consequences

The maximum sentence for a juvenile homicide in Colombia is eight years. An adult can face up to 50 years behind bars. Using minors “is an old custom” in the country that “clearly seeks impunity and to take advantage of their marginalized status,” says criminal lawyer Francisco Bernate. Bernate suggests that the brain development of children and adolescents is a determining factor in these cases. A minor under 18 years of age “does not have the full capacity to understand” the “consequences of his actions.” “Not only in Colombia, (but) in most countries around the world, and as required by international treaties, they receive different treatment than adults,” he says. Prosecutor Camargo explained that, unlike the penal code, which has a punitive approach, the legal framework for minors includes educational and restorative sanctions. They don’t go to prison, but rather to specialized centers.

Bad Memories

On March 22, 1990, Communist Party presidential candidate Bernardo Jaramillo was about to board a flight. Despite being accompanied by bodyguards, he was shot at point-blank range and killed at the airport. The young man wielding the weapon was 16 years old. “That boy was detained for a little over a year and in 1992 he was found shot dead alongside his father in the trunk of a car in Medellín,” says journalist and academic Jorge Cardona. The author of the book “Days of Memory,” which recounts the violent events that marked Colombia between 1986 and 1991, recounts two more cases. Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla was murdered by a 16-year-old in 1984, and Carlos Pizarro, a former M-19 guerrilla and presidential candidate, was shot by another 20-year-old man on an airplane in 1990. These cases have not been fully resolved.