Maria Ossa de Amador: Conspirator and Patriot for Independence from Colombia

The life of María Ossa de Amador is a lesson in patriotism that is an example for current generations. María Ossa de Amador, known as the “Mother of the Country” in Panama, was a central figure in the events leading to Panama’s separation from Colombia in 1903. Her role was fundamental both in the creation of national symbols and in the strategic preparations for Panamanian independence from Colombia. Although she is mainly known for the creation of the first two flags of the republic, her participation in the separatist movement went much further.

She was part of the group of conspirators from the beginning. She concealed meetings in her house, planned strategies to distract the authorities, recruited sympathizers for the cause and encouraged decisive action at the right moment. “Such was the intervention of Mrs. María Ossa de Amador in the creation of the Panamanian homeland and her very meritorious participation as a conspirator and patriot.” The historian Ernesto J. Castillero Reyes in an article entitled Doña María Ossa de Amador – Authentic heroine of our independence, published by the magazine Lotería No. 88 of September 1948, describes her as follows:

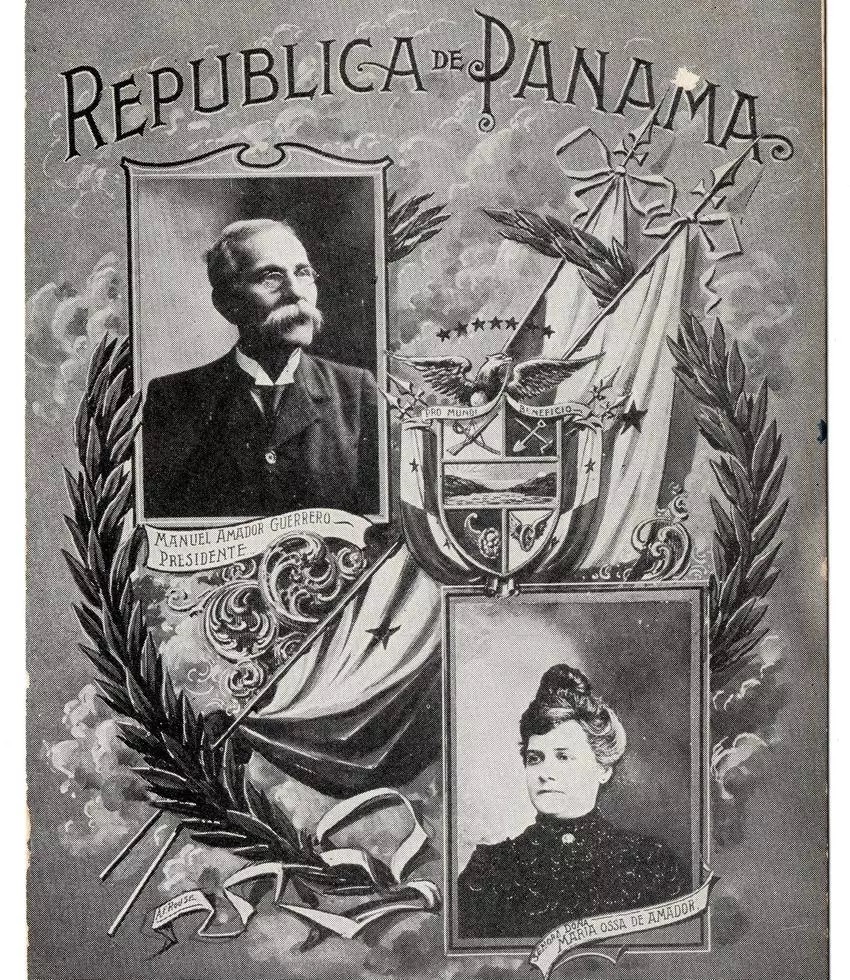

“Such was the intervention of Mrs. María Ossa de Amador in the creation of the Panamanian homeland and her very meritorious participation as a conspirator and patriot .” She was born on March 2, 1855 into a family of the Isthmus elite. At the age of 17, on February 6, 1872, she married Dr. Manuel Amador Guerrero (22 years her senior). Everyone who knew her agreed about her beauty and charm. Her education and privileged environment allowed her to develop a deep sense of patriotism and a commitment to the ideals of independence that marked the 19th century in Latin America. The couple had two children: Raúl Arturo and Elmira María.

Family Photo Above: The Amador family: seated, María Ossa de Amador (l) and her daughter Elmira. Standing, Dr. Amador Guerrero (l) and his son Paul.

Conspirator and Patriot

The story that María Ossa herself, tells Octavio Méndez Pereira of the events of November 3, 1903, is very rich and illuminating, so just as Castillero Reyes does in his text, I let her speak directly: “That day,” she says, “my husband went out into the street as soon as he received the news, at 6 a.m. without even having breakfast. He went to talk, as I later learned, with some conspirators, determined that the coup that was planned for the 28th of the same month would be carried out immediately. When he returned about two hours later, I found him lying in the hammock in his room in his shirtsleeves, with his hands clasped over his forehead in an attitude of deep concern.

—What’s wrong? I asked him.

“I think all is lost,” he told me. “Some of my companions are wavering and I think they’ll leave us.”

So I started to encourage him and give him the confidence he needs in those difficult times.

—If they leave you, you have to proceed. There is no turning back now. Go on, get up and fight.

I advised him to go immediately to see Mr. Prescott, a person of absolute confidence, who was the very person who had given him the news of the arrival of the Colombian cruiser in Colon. Mr. Prescott was married to a Panamanian woman, had served for many years as a telegraph operator for the Panama Rail Road and was currently serving as Sub-Superintendent of the same company. He could therefore communicate secretly and directly with Superintendent Shaler, who was in Colon, to ask him not to allow the Colombian troops to come to Panama under any circumstances.

Amador agreed to my suggestions and managed to obtain through Prescott that Shaler accede to his request. The Colombian generals searched in vain for Mr. Shaler and neither he in Colon nor Prescott in Panama facilitated the embarkation of the troops. There was even talk of blowing up one of the bridges, the Barbacoas bridge, to prevent the train from passing, in case it was not possible to prevent the transport of the trains.

As soon as Amador left my house to go and see Prescott, I took a carriage and went to the house of our friend José Agustín Arango and then to that of Espinosa, who was married to a first cousin of mine, and I urged them all to proceed without losing time, since they were already committed to their lives and it was not the time to stop and meditate. I am left with the satisfaction that my voice of encouragement managed to animate and rekindle the enthusiasm of these two patriots.” The rest is history. That same night the Municipal Council met and approved independence. The Panamanian population celebrated with music, fireworks and revolver shots as the newly-released flag passed by, which, as we know, was made by the hands of María Ossa de Amador. Now let’s get to it.

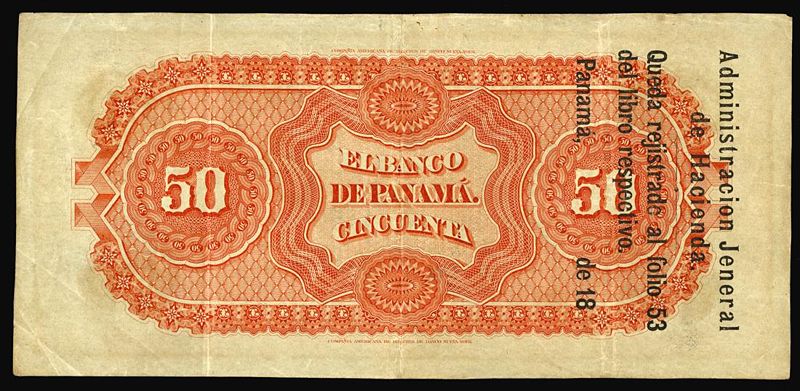

The making of the first flag

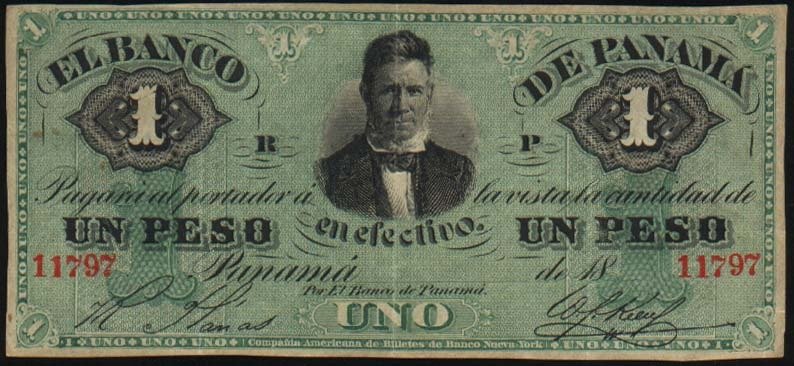

To recount the circumstances of the design and making of the first flag of Panama, it should first be said that Philipe Bunau-Varilla had designed a flag inspired by that of the United States, which was sewn by his wife and given to Amador Guerrero at their meeting in Washington in October 1903.

This flag was unanimously rejected by the separatist group, explains Amador Guerrero, “Mrs. B. Varilla’s flag project was unanimously rejected, first because she is a foreign lady, and then because in colors, design and idea it differs very little from the American one. But the problem is that they want me to make one or get someone to make one. The first is impossible because I lack an idea and the second is otherwise exposed ,” according to Ernesto Castillero Reyes , who tells us how the design was first and then the making by the protagonists in his book Historia de los Símbolos de la patria panameña.

The first story, that of the design, he learned directly from a letter addressed to him by Manuel Encarnación Amador, son of Dr. Amador with his first wife, who was at his father’s house with María when he arrived with the news of the need for a flag. Manuel Encarnación himself recounted in a letter dated September 7, 1951 addressed to the historian, how he designed the national flag in the following way:

“After these words I stood up energetically and invited them to follow me to an old desk that my father kept in perfect order for the purposes of his small securities business. Once there my eyes caught the presence of a specimen of two-color pencils that came from Vienna, always colored with exquisite care.

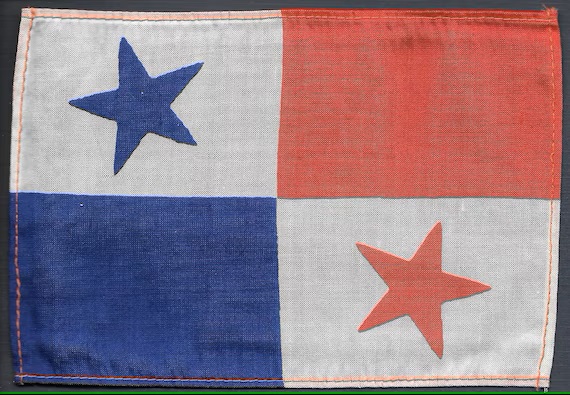

Intuitively I took it in my hand and, taking a sheet of white paper from a drawer, I drew a vertical line to simulate a flagpole, then to the right, to simulate a flag, I drew an oblong quadrilateral. On this I drew two cross-shaped lines along its entire length, which gave me four quarters; in the upper left quarter, next to the flagpole, I roughly traced the outline of a five-pointed star, which I dyed blue on its entire surface, and in the lower right quarter I traced a star that I had in red. The quarters opposite the stars in a vertical direction I dyed completely the color of the corresponding stars.

The design, thus illuminated, I displayed before the eyes of my father and his wife, and after a few seconds of contemplation he asked me this question, which I answered with a certain blush of humility more or less like this: ‘I must confess in all truth that from the moment I stood up and asked you to accompany me here, I have no concrete conception of symbolism, nor even up to this moment, regarding this strange creation. Perhaps we can squeeze out of it its own meaning and attribute to it marvelous attributes.

For the moment, don’t we see in it something like the reflection of the present political moment? The traditional political parties that have fought in bloody wars embrace each other in the field of peace to build a country. Note that there is not more of one color of those that represent the parties than of the other, and almost twice as much white as those add up to. ‘After a few seconds of reflection my father said: Well, and the stars? “Well, these,” I replied, “symbolize: the blue symbolizes purity and honesty that will govern the civic life of the country; and the red symbolizes authority and law that will enforce the rule of these virtues.

My father pulled me towards him and holding me tightly said: ‘Very well, very well: Mary, make the flag right away; we may need it at any moment.’ “This is how María Ossa de Amador got down to work on November 1st. She thought of everything. Since the colors white, blue and red were not on the Colombian flag, buying fleece in those colors could arouse suspicion, so she decided to buy them in different stores. She bought the white fleece at the French Bazaar, the blue at La Dalia and the red at La Villa de París. She also decided not to make the flag at her house because the authorities suspected a possible plot and, as if that were not enough, José Domingo de Obaldía, the Governor of the department, lived in the Amador Guerrero house. There was no way to make it there without him noticing.

“On the morning of November 2nd, I packed a package of the wool and went to the house of my brother, Don Jerónimo Ossa, married to Doña Angélica B. de Ossa. This house was located on what is now Avenida Sur, on the corner next to the electric plant. There I found my sister-in-law, and after having promised me the strictest secrecy, I confided to her what was in question. We agreed to begin making the flag, we cut the materials for two, since I had bought enough fabric for it. To be on the safe side, we decided not to do the work at his house but to go to another one next door, also located on Avenida Sur, then owned by Messrs. Ehrman and Co., and known under the name of Casa Tangui. It was completely unoccupied, therefore, closed, and to enter it we had to climb through a small window that looked out onto the patio by going up a ladder.

A maid of my sister-in-law called Águeda also gave us a hand-held sewing machine through the window. There being no furniture, we placed the sewing machine on a small box and cut out the squares and stars on the floor. As you might expect, we worked hard and quickly finished the two flags; I then wrapped them in the papers that had been used to carry the flannels; I took a carriage and went to my house, a room located in the Plaza de Catedral”.

Events moved quickly and on November 3, 1903, the independence of the department of Panama was proclaimed. The people received the first flag of the new nation from the hands of María Ossa de Amador, which was paraded through the capital city amid shouts of joy by Alejandro de la Guardia, the first Panamanian standard-bearer. The flag was baptized on December 20, 1903 in the Plaza de Armas —now Plaza de Francia— by the Reverend Father Fray Bernardino de la Concepción García, army chaplain. The flag’s sponsors were Dr. Gerardo Ortega with Mrs. Lastenia de Lewis and Mr. José Agustín Arango with Mrs. Manuela de Arosemena.

First Lady and her legacy

Her resourcefulness and ability to handle difficult situations reflect the essential role of women in Panamanian history. Often relegated to the background in official records, women like María Ossa de Amador demonstrated their importance in the political and social life of the time. María’s involvement was not only fundamental to the cause of independence, but also inspired future generations of Panamanians to value and respect their heritage and national symbols.

Once independence was consolidated, María Ossa de Amador assumed the role of First Lady of the Republic, where she continued to promote the values of the new nation. She hosted official events and received international dignitaries, projecting an image of a sovereign country committed to its future. Her role as First Lady was not limited to public appearances; she also took on social support tasks and promoted the values of education and solidarity.

After her death, Octavio Méndez Pereira published, “I, who knew her so well and who received her written correspondence until her last days, know of her concerns and her dreams of seeing the Republic that she helped form become a mature democracy.” After her husband’s death in 1909, Maria Ossa traveled to visit various family members in the United States and Europe. During this time she advocated for the education of women, as well as religion as a moral compass to guide them.

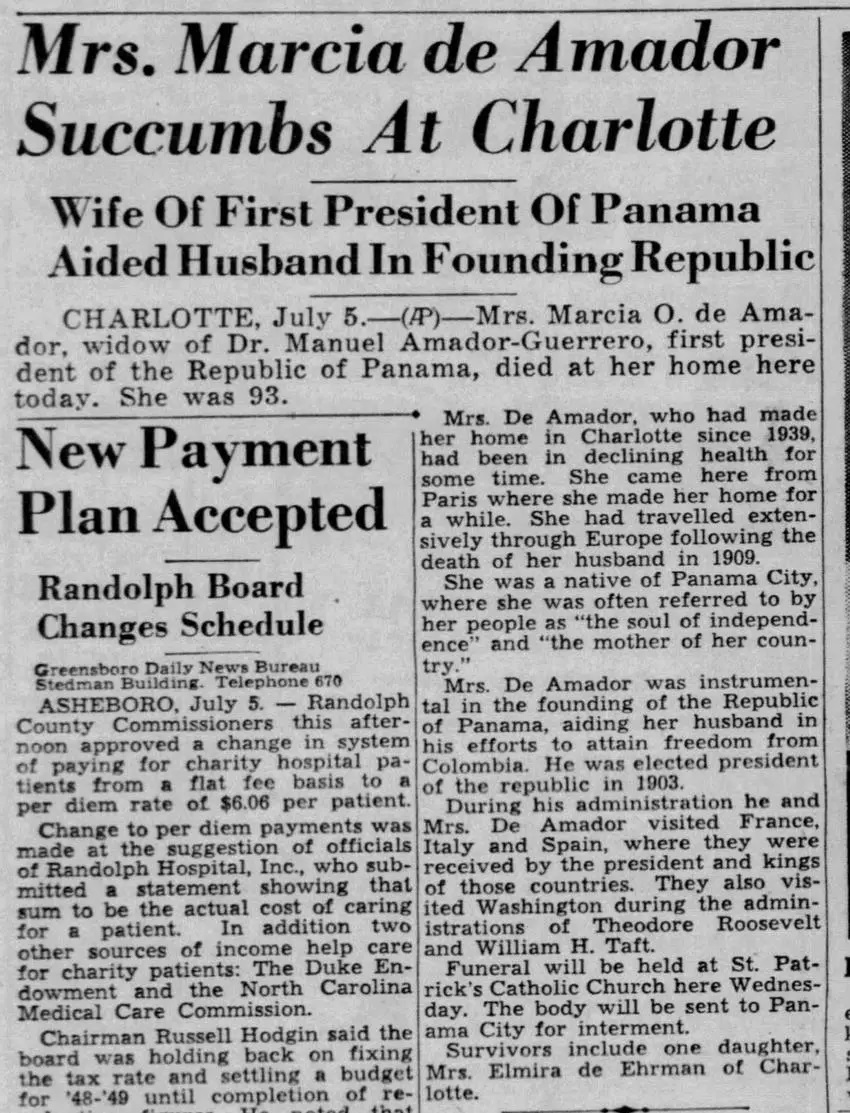

She lived in Paris until 1939, when she moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, where she died at the age of 93 on July 5, 1948. After her death, Octavio Méndez Pereira published, “I, who knew her so well and who received her written correspondence until her last days, know of her concerns and her dreams of seeing the Republic that she helped to form become a mature democracy.” In 1935, Flag Day was first celebrated in her honor on November 4, and in 1941, the National Assembly of Panama passed Public Law 60 to recognize her contributions to the nation. The Panama flag was baptized on December 20, 1903 in the Plaza de Armas (Plaza de Francia).

María Ossa de Amador is remembered every November 4, a date that was initially celebrated as Flag Day and is now commemorated as the Day of National Symbols. Her contribution to the history of Panama continues to be remembered and valued, not only for the symbol of the flag that she helped create, but also for her bravery and her fundamental role in the key moments of independence.

The legacy of María Ossa de Amador extends beyond the boundaries of her time. Her story is a reminder of the importance of citizen participation and the role of women in decisive moments in the history of a country.

News and Record clipping from July 6, 1948, where the news of the death of Mrs. María Ossa de Amador is published.

To delve deeper into this topic look for the book: History of the symbols of the Panamanian homeland by Ernesto J. Castillero Reyes. Knowing the past helps us to understand our present.