Panama’s Caribbean Corridor Highway Threatens Environentally Protected Areas

A lawsuit has temporarily stalled construction on a controversial highway project in north-central Panama, which allegedly bypassed environmental regulations and could damage several protected areas along the Caribbean coast. The highway, known as the “Caribbean Corridor,” is supposed to travel 28.4 kilometers (17.6 miles) from the towns of Quebrada Ancha to María Chiquita, with the goal of increasing tourism and local commerce on the coast of Colón province. But the highway would also pass by three protected areas and didn’t carry out adequate studies to make sure they won’t be harmed by construction, conservation groups claim.

“We have to value our natural resources and look for other development alternatives that are more sustainable, that are friendlier to the environment and that benefit a greater number of people,” said Guido Berguido, biologist and executive director for Adopt a Panama Rainforest Association. Construction plans from the Ministry of Public Works (MOP) and builder Transeq-Estrella Consortium show that the highway, which will cost around $91 million, could endanger Portobelo National Park, Chagres National Park, Sierra Llorona Private Reserve and the Panama Canal watershed that includes Gatun Lake and the Panama Canal. Together, the protected areas account for approximately 165,129 hectares (408,042 acres) of land.

One lawsuit, submitted in January by the Alliance for Conservation and Development, focuses on the MOP’s decision to divide highway construction into sections, tendering each one separately and requiring environmental impact studies for each one. The project’s classification allowed some construction on the second section of the project to move forward before a consultation process with residents near the highway could be completed. During that process, residents would have met with officials to discuss the potential impacts of the project and had an opportunity to reject the terms of the project, forcing builders to come up with a new route. A criminal complaint was also filed with the prosecutor’s office for crimes against the environment. However, details of the complaint haven’t been made public.

Cristóbal Valencia, president of the Portobelo Chamber of Tourism, was quoted in local media saying that the project was necessary for bringing development to the area, and that environmental impacts were inevitable in any project of this kind. “We’re not opposed to development,” said Susana Serracín, president of the Alliance for Conservation and Development and the environmental lawyer who filed the lawsuit. “We believe communities need better roads, better highways. We think that all this is a fair aspiration of all the populations that surround that area. But it’s not the right way to do things. We think that the legal framework must be respected.”

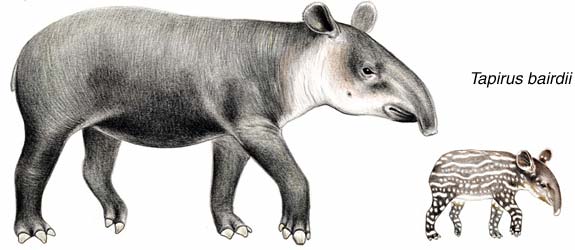

One of the protected areas that could be impacted, Chagres National Park, was largely created to protect the Chagres River, a main source of clean drinking water for the country, including Panama City. It’s also the source for almost half of the water used for the Panama Canal. Lake Alajuela, a reservoir connected to the canal, is also located inside the park. The current highway route won’t pass through the park but instead affect the park’s buffer zone, conservationists said. That could still threaten species like the jaguar (Panthera onca), tapir (Tapiridae) and red spider monkey (Ateles paniscus), among others. It would also interrupt the Mesoamerican biological corridor, a series of connected protected areas throughout Central America that allow migratory species to travel between North and South America.

Despite the court’s ruling on the lawsuit to temporarily suspend construction last month, the MOP reportedly moved forward with consultations in Portobelo and other nearby communities. But even with approval from the communities, the project won’t move forward until the court deems that it has met higher environmental standards. “From our perspective, based on the entire impact of such a delicate area, with so much biodiversity and a Mesoamerican biological corridor that is so fragile, this environmental impact study should determine that this work is not viable and is not convenient at this time,” Berguido said.