La Prensa to appeal $500,000 award to Roberto Duran

No one has the right to use, without their consent, the image of another person to recommend that they go to eat in this or that restaurant, buy a product, use a service or visit a certain hotel. For example, if you sell sports equipment, you could not use the image of New York Yankees star player Aaron Judge in an ad saying that Judge recommends his store because they sell the best bats and handles there. To do this, you would have to have express authorization because you would be using the image of a famous athlete who recommends a product that you sell. But if you, as the owner of the store, decide to advertise in the sports segment of a television channel or in the sports section of a newspaper and your ad appears next to a news story or report on Judge, there is no conflict, nor abuse of the use of the image. The athlete’s image is used to illustrate journalistic content, which can be biographical or news, and advertising appears in the spaces designated for it. At no time is it inferred or interpreted that the athlete is recommending or endorsing the advertiser in any way.

One only has to replace Judge with Roberto “Mano de Piedra” Durán to understand that the sentence against Corporación La Prensa (Corprensa) is nonsense and, worse still, establishes a disastrous precedent against freedom of expression and of the press and against the right to access to information. Consider for a moment the logical consequence that any public figure could now claim damages and lost profits when a media outlet or a citizen uses his image to speak about matters of public interest. Tomorrow, the President of the Republic could sue this newspaper or another media outlet on the grounds that his image is being used to sell newspapers and the advertisers who were on that page, print or on the web, benefited from the image. of the president. This would end the freedom of the press and of expression.

Mano de Piedra is a globally recognized athlete, he is a public figure, with numerous, wide, diverse, extensive reports, news, interviews, and books, published about him, his sports career, and even his successes and failures in other aspects of his life. As such, anyone has the right to write about Durán, with or without his authorization, even if it were a question of writing a biographical book that did not have the boxer’s authorization. In the United States there is a multiplicity of cases referring to “unauthorized biographies” of famous people, from politicians and businessmen to artists and athletes. Many of their authors have suffered lawsuits, and the usual thing is that the courts defend the right of the author to write them, publish them, and earn money from the sale of the works.

Readers will remember Noriega’s lawsuit against video game producer Activision for his unauthorized appearance in the game Call of Duty: Black Ops II . The lawsuit was dismissed for being considered a public figure. A similar result was obtained by the lawyers Mossak and Fonseca in their lawsuit against Netflix as a result of the feature film The Laundromat. I mention these cases because they are Panamanian figures. Although the cases are not the same, they are third parties profiting in some way from the use of the image or story of people who did not authorize it for such use. The reason is that US jurisprudence has regularly and strongly established the right of citizens in these cases to “fictionalize” historical figures and to deal with issues of public interest in any of the arts.

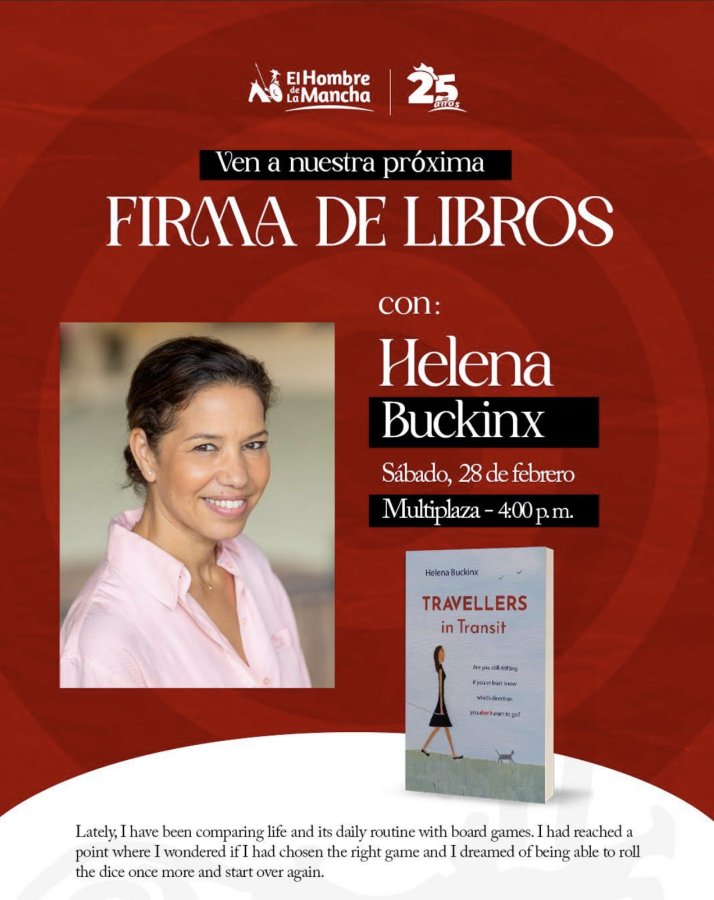

If La Prensa had published an advertisement with the image of Mano de Piedra without his authorization saying: “Read La Prensa, the best newspaper in Panama”; or if Super Xtra had made an ad with the image of Mano de Piedra, without his authorization, saying: “Buy at Super Xtra where prices are knocked out”, then it could speak of use and abuse of his image for profit. However, this was not the case. La Prensa, by journalist Guido Bilbao, published a 30-page collectible biography of Roberto “Mano de Piedra” (Hands of Stone) Durán, based on publicly available material, including his “authorized” biographical book. In a certain sense, it can even be said that La Prensa promoted the figure of the athlete for free, particularly for younger readers who did not experience his achievements. The biography was inserted at no additional cost in the printed newspaper for one month, and in spaces designated for such, there could be advertising from one or more advertisers. Curiously, several years ago Mano de Piedra appeared on the cover of K Magazine, and despite the fact that Durán did not receive any emolument for having used his image, no claims were received despite the fact that the magazine was usually sold in different stores. of the locality and was inserted without additional cost to the subscribers.

We are then facing an exaggerated demand ($5 million in damages was requested), unfounded (biographical content about a public person) and intimidating (using it as a mechanism to generate self-censorship). The $500,000 sentence, although 10 times less than what was claimed, is completely disproportionate to the cost of the product (about $70,000) and Super Xtra’s ad revenue of only $20,000. In addition, Corprensa was able to demonstrate that there was no increase in newspaper sales during the period in which the biographical pages were inserted.

It is for all of the above, and being consistent with the democratic principles that our organization has defended for the last 42 years, that we have made the decision to instruct our lawyers to appeal the judge’s ruling before the Supreme Court of Justice, in cassation.

In Leviticus there is a maxim that every judge should have on his or her desk: “You shall judge your neighbor with justice, not letting yourself be carried away by the gifts of the rich or by the tears of the poor”, to which should be added “nor by the popularity of the famous.

The author is president of Corprensa.