A Life from Brooklyn to Darien and Beyond

By Mark Scheinbaum

MIAMI)—It was the spring of 2006 when a Romanian-born businessman, former tennis pro, actor, and my friend since high school Robert Lempert declared, “This is outrageous! What Panama has to have is a U.S.-style title insurance company. I am starting one!”

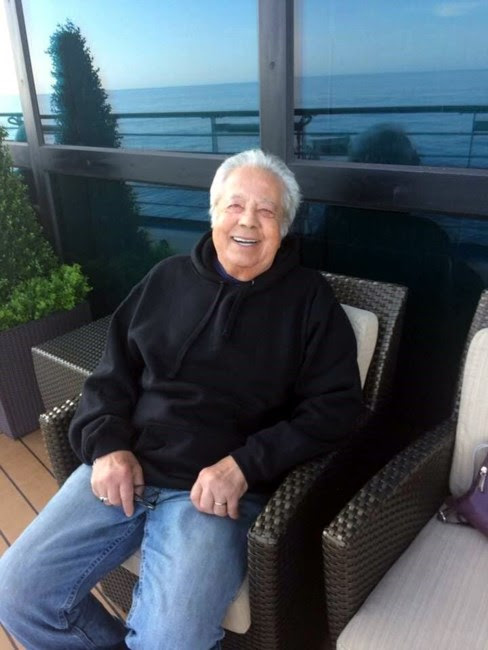

Bob Lempert died after a long illness in his adopted hometown of Brooklyn, NY on March 19, at age 70. The eulogies of his wife Susan and son Danny affirmed what most of us already knew: Mr. Lempert was headstrong, impulsive, fervent about what he thought was right, and quick to tell you what he thought was wrong.

But as the career of the young athlete from Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, and the tennis scholarship micro-biology student at Bowling Green (Ohio) University evolved into restaurateur and successful real estate owner, he probably touched the lives of thousands in the small and proud Central American Republic of Panama in hidden ways.

With business and real estate interests in New York, New Jersey, and Panama among other ventures (he was once an Equity actor with roles on a TV soap opera), his heart and determination was touched by poor, hard-working people in Panama and elsewhere who, through bad luck or crass political manipulation, were denied ownership of the property their families had cleared, farmed, and often improved over generations.

On a visit with me to three small schools near the hamlet of Torti, Panama (90 minutes past Chepo, almost to the border of Darien), Mr. Lempert was a guest of our Panama Canal Kiwanis Club. The widow of a local farmer had donated land to Kiwanis to build an elementary school called La Tosca. The land would be Kiwanis property and the school and its one-room schoolhouse and single teacher for grades Kindergarten through six would be administered by The Ministry of Education.

He never forgot how his dad, working as a park groundskeeper, managed to introduce him to tennis on vacant courts in Romania during slow hours. It sparked his lifelong love for competitive individual and team sports. After helping to organize a soccer match, he decided the kids, many barefoot, needed a ping pong table and equipment. It was typical Lempert. A few weeks later the table tennis gear arrived and was delivered to the youngsters.

Tax avoiders

But Lempert also learned about colonists whose parents, grandparents, or in some cases great-grandparents were sometimes classified as “squatters”, even though documents from the national water department (IDAAN) showed that in many portions of rural Panama, and even on some of the indigenous ”reservations” (comarcas), the alleged wealthy “landowners” and their influential families had never done anything, including paying taxes. It was all anecdotal at first, but with the help of a young attorney, Ezra “Zuri” Angel, Lempert and some friends researched the history of the land crisis which had sparkled rural uprisings from Chiapas in Mexico, to much of Latin America.

Lempert and his buddies started the process of getting licensed as “title agents” at a program in Orlando, Florida at their own expense (but underwritten initially by Lempert) and consulted with experts trained in Spain on the history of peasant land rights in the Americas.

Sure, there was an ulterior business motive regarding the thousands of ex-pats moving to luxury high rises in Panama City and asking for “title insurance” in the way they would protect their land titles in the USA, Canada, and other countries. But after meeting with the top officials in Panama at the Public Registry, and with representatives of the Bern family enterprises, he was encouraged.

The same rules which could provide a sense of security to a couple from Boston or Toronto buying a condo in a new building on Avenida Balboa could have a residual effect of establishing a precedent for obtaining legal, written, documented rights to disenfranchised rural Panamanians.

As a political scientist supposedly savvy about Latin America and the Caribbean, (four years later I was tapped to teach two classes in Latin American Politics at the University of Louisville’s Panama, Quality Leadership Program) I had my doubts about any group of “gringos” cracking three centuries of Spanish cultural and legal influence, but Lempert would not permit negativity.

“There are one or two title insurance companies from the U.S. operating out of Costa Rica, they have started to prospect for clients in Panama, and this is a market ready to pop. Buyers want title insurance. We are going to provide it. No one else is willing to take the chance. We have to do this,” was the Lempert view.

Enter the academic works of Brazilian-born sociologist Jose de Souza Martins.

As an author and human rights activist who had already established his reputation in Brazil, de Souza Martins was a United Nations human rights official whose academic works, speeches, and videos were influencing a new generation of public administrators, land reformers, and political activists in the Hemisphere.

‘You have to read this!” Lempert told me after a board meeting of the fledgling title company and tossed a photocopy of one of de Souza’s articles. The Brooklyn kid became a mini-expert on land reform. He had come a long way from the teenager who, upon arriving in New York at age 13, spoke almost no English. He literally told people about his net worth with the statement (as recounted in his son’s eulogy speech about his dad) “What do I have? I have THIS!!” tugging on a worn tee shirt. When queried by a potential employer, he pointed to the shirt on his back.

In Lempert’s mind, the possibility of a rather low-cost title insurance policy to bring peace of mind to a retiree buying an apartment in a foreign land could also serve as a catalyst for land reform in Panama.

Fast forward a few years, and the title insurance common to people in Chicago, Denver, Montreal or Fort Lauderdale never came to fruition.

But as some developers, real estate salesmen, and bankers in Panama explained to me, the concept of removing a “cloud on title” which could lead to ownership questions months or years after a purchase, in a way were starting change.

Some of the larger Panama banks, and perhaps with a push from the foreign home offices of banks such as HSBC and Scotiabank, were putting much more detailed background checks and research into mortgage application approvals. In addition to the usual income standards and residency or corporate (“anonymous society/S.A.”) issues, the banks were also taking a closer look at who really owned underlying lands and who might have dormant claims to undeveloped or developed property.

As in the United Kingdom, Mexico and other nations, the owner of a house might or might not have true ownership of the soil beneath the home. In some cases, the landowner might have some rights in perpetuity for themselves or their heirs. Case-by-case reviews allegedly or supposedly were becoming more common.

It was the infancy of consumer protection for those who were losing deposits on “pre-construction” deals, rather than just lip service. The inconsistencies and fraudulent claims still exist, but only history will tell if Robert Lempert and his stubborn exploration of land reform possibilities will at least be a footnote to more just and equitable land rights in Panama, or elsewhere.

Admittedly, the Panama connection was not a major act in the Lempert saga, but one wonders if we should add “sociologist” to his legacy.

Mark Scheinbaum, teaches Political Science and International Relations at Floridia International University. He is managing director of Shearson Financial Services LLC., Hhis views do not reflect those of his firm or clients.