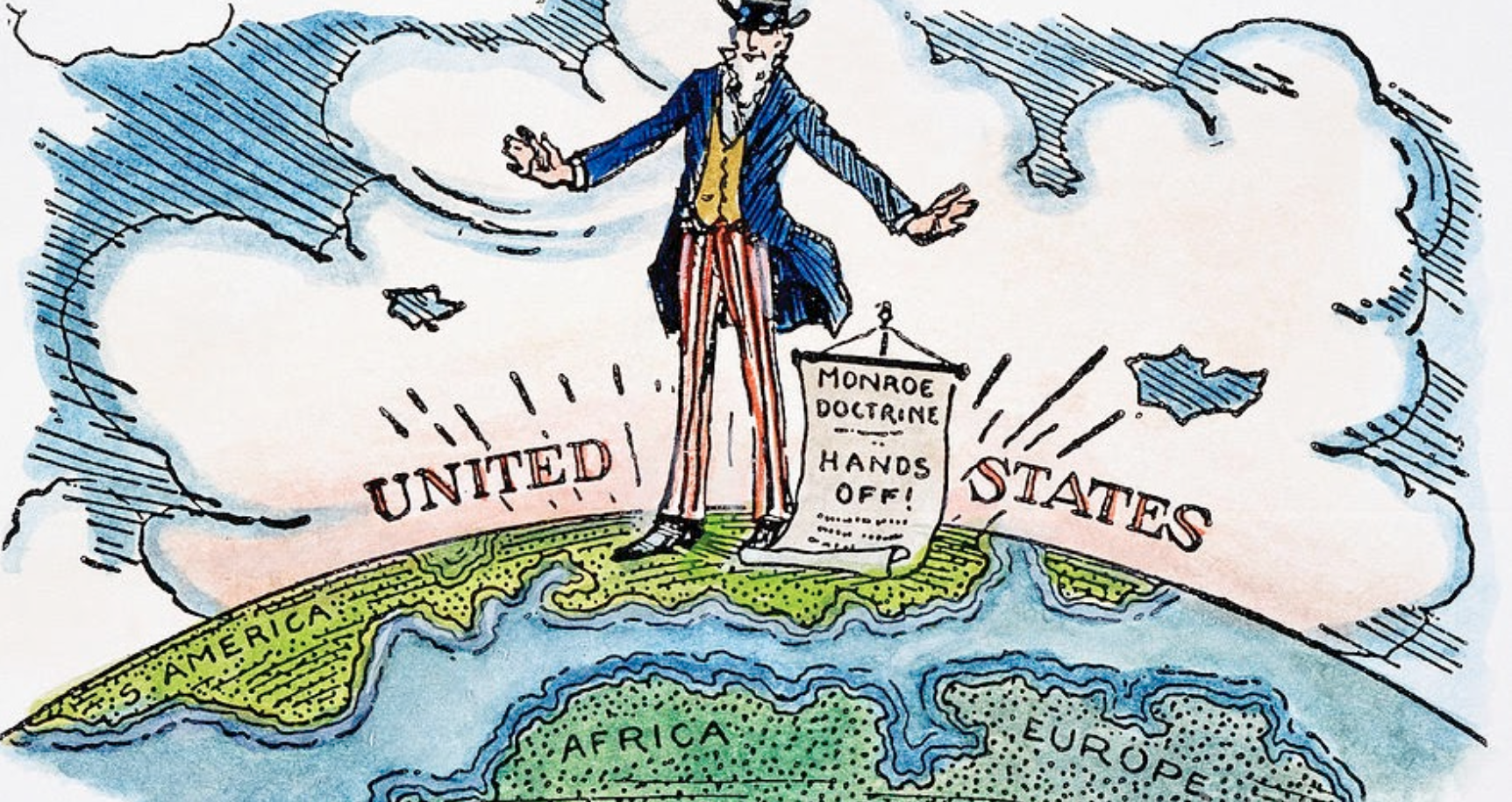

MEDIAWATCH; Monroe Doctrine ghost haunts White House

By Michael Shifter in the Globe & Mail Feb. 3

Michael Shifter is president of the Inter-American Dialogue and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, where he teaches Latin American politics.

The unfolding drama in Venezuela shows that former U.S secretary of state John Kerry was right when he formally retired the Monroe Doctrine in 2013 in a speech at the OAS. Originally intended as a warning against European powers seeking influence in Latin America, this 19th-century doctrine became virtually synonymous with United States unilateral intervention in the region.

For decades, Washington treated Latin America and the Caribbean as its backyard, invading a host of countries and supporting coups against unfriendly governments throughout the hemisphere. By the time of Mr. Kerry’s speech, however, the doctrine had been rendered obsolete by changes in Latin America, the US, and the world.

And yet, the discourse of part of the media, pundits, and policymakers in the US. regarding the Venezuelan crisis seems to revive that bygone era of unilateral interventionism in Latin America. In the last few days, domestic and international factors have dramatically increased pressure on Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro, who succeeded Hugo Chavez in 2013 and has presided over the utter ruin of the oil-rich nation.

The US has an opportunity to play a constructive role in fostering a peaceful, democratic transition in Venezuela. It can only do so, however, if Washington resists the temptation of acting alone and behaves as part of a broad coalition with other Latin American countries. The good news is many governments in the region have joined the US in condemning Mr. Maduro and recognizing Juan Guaido –opposition leader and president of the democratically elected National Assembly – as interim president on Jan. 23.

The Lima Group, created in 2017 to address the Venezuela crisis and comprised of 14 countries – including Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, and Chile – has been key in isolating Mr. Maduro internationally. On Jan. 4, the bloc urged the dictator not to take the presidential oath for a second term and instead cede power to the opposition-controlled National Assembly until free and fair elections could be held. The unprecedented exodus of Venezuelan migrants and refugees to many countries in the region – the UN estimates over 3 million e – helped increase pressure on governments to adopt a stronger position.

In addition, the OAS and it’s Secretary-General, Luis Almagro, has been forceful in its condemnation of the Maduro regime and its call for restoring democratic rule in Venezuela.

Almagro’s outspoken stance, along with Lima Group demands, has buttressed the Trump administration’s argument and justified sanctions and other punitive measures.

The OAS Human Rights Commission and its careful documentation of widespread abuses also help make the US case against Maduro. Latin America’s important efforts have given the US administration a chance to reaffirm core American values.

The Hawks

There are, of course, reasons to be concerned that the impulses for unilateral intervention have not been extinguished. Back in 2017, to the surprise of his closest foreign-policy advisers, President Trump referred to a possible “military option” in Venezuela. Months later, then-secretary of state Rex Tillerson defended the Monroe Doctrine as a successful foreign-policy approach, ignoring its negative image in Latin America.

Though a U.S. military intervention in Venezuela is highly improbable, influential players such as National Security Advisor John Bolton and Florida Republican Senator Marco Rubio continue to mention it, perhaps as a way of posturing and escalating pressure on Mr. Maduro. Mr. Bolton’s close association with the disastrous U.S.-led Iraq war and his past statements supporting regime change in Iran do not inspire confidence in restraint.

The risk is that maintaining the possibility of a U.S. armed intervention in Venezuela, with echoes of the Monroe Doctrine, could undermine the Latin American coalition that has been forged and today holds the promise of success. It could also splinter the Lima Group itself into more hardline and moderate governments, which would weaken unity and diminish the bloc’s effectiveness.

Counterproductive

This is a critical moment in the Venezuela crisis – hopeful yet uncertain. Moving forward, senior Trump administration officials would be wise to devote more time with their Latin American counterparts, issuing joint statements and coordinating actions to pressure the regime and advance Mr. Guaido’s efforts at reconciliation. Posturing about the U.S.’s power and influence in Venezuela evokes a 19th-century doctrine that has long been irrelevant and is counterproductive.

If the initiative of the Lima Group, the OAS and the United States working together ends up contributing to the restoration of democratic governance in Venezuela, that could well be the start of a more constructive U.S.-Latin American relationship.

Michael Shifter is an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service