Panama Cobre Copper Mine by George Bauer - Comments Welcome

The Cobre Panama Copper Mine To be, or not to be? by George Bauer

The impact of the shuttering of First Quantum’s Cobre Panama copper mine is the “elephant in

the room” of the build-up to Panama’s impending, May 5, presidential election. Likely, whoever wins

will then be faced with an apparently irremediable fiscal challenge, with little money in the bank, huge

loans to service, high interest rates, voters calling for hand-outs promised when he was on the campaign

trail, high unemployment etc. If the mine remains closed, then Panama will also be hit with paying “fair

compensation” to First Quantum, the cost of closing the mine and remediating the site in an

environmentally friendly manner, with no more money from the mine for government, employees,

suppliers, contractors et al, difficulty financing large, government and private, projects, increasing

unemployment etc. If the mine is not reopened, this could impoverish Panamanians during the next

presidential term and for generations to come.

the room” of the build-up to Panama’s impending, May 5, presidential election. Likely, whoever wins

will then be faced with an apparently irremediable fiscal challenge, with little money in the bank, huge

loans to service, high interest rates, voters calling for hand-outs promised when he was on the campaign

trail, high unemployment etc. If the mine remains closed, then Panama will also be hit with paying “fair

compensation” to First Quantum, the cost of closing the mine and remediating the site in an

environmentally friendly manner, with no more money from the mine for government, employees,

suppliers, contractors et al, difficulty financing large, government and private, projects, increasing

unemployment etc. If the mine is not reopened, this could impoverish Panamanians during the next

presidential term and for generations to come.

Though indigenous artisanal mining of gold and copper in Panama dates back almost two

thousand years, it was not until just after the Spanish conquest, when Columbus found gold in Veraguas in

1503, that Panama had its first “gold rush”. Mining was then almost continuous, with recent mines

including the Santa Rosa Gold mine, near Santiago (ceased production in 1999, planned to re-open

recently, but now shut-down by the November 2023 Supreme Court decision), Petaquilla Gold near

Penonome (producing from 2009 to 2014, now closed), and First Quantum Minerals’ (“FQM”) Cobre

Panama copper mine, in Colon Province, near Coclesito.

thousand years, it was not until just after the Spanish conquest, when Columbus found gold in Veraguas in

1503, that Panama had its first “gold rush”. Mining was then almost continuous, with recent mines

including the Santa Rosa Gold mine, near Santiago (ceased production in 1999, planned to re-open

recently, but now shut-down by the November 2023 Supreme Court decision), Petaquilla Gold near

Penonome (producing from 2009 to 2014, now closed), and First Quantum Minerals’ (“FQM”) Cobre

Panama copper mine, in Colon Province, near Coclesito.

Q. When do you know that a banana republic is going down the tubes?

A. When there are no bananas in the supermarket.

A. When there are no bananas in the supermarket.

The International Energy Agency, in its influential 2020 Report, “Net Zero 2050”, commented

that for this to be achieved, the World would need to produce five times as much copper each year by this

date. It typically takes some sixteen years between discovery and first copper production from a new

mine. Mankind looks most unlikely to meet this target for production of copper, and other minerals

critical for “going green”. Cobre Panama should be a small, but significant, contributor to “saving the

planet”.

that for this to be achieved, the World would need to produce five times as much copper each year by this

date. It typically takes some sixteen years between discovery and first copper production from a new

mine. Mankind looks most unlikely to meet this target for production of copper, and other minerals

critical for “going green”. Cobre Panama should be a small, but significant, contributor to “saving the

planet”.

Only fourteen nations, out of 156 listed, have a less equal distribution of wealth and income (i.e.

higher “GINI coefficient”) than Panama. For this to be corrected so as to improve the prospects of the

higher “GINI coefficient”) than Panama. For this to be corrected so as to improve the prospects of the

vast majority of the Panamanian people, Panama needs more high-valued-added jobs, at different levels,

which, realistically, can only come from export-oriented, high initial investment projects, for which

Panama has neither the skills nor the money to invest. Cobre Panama, and other mining prospects, offer

just such opportunities to Panama and its citizens.

which, realistically, can only come from export-oriented, high initial investment projects, for which

Panama has neither the skills nor the money to invest. Cobre Panama, and other mining prospects, offer

just such opportunities to Panama and its citizens.

During the first “Presidential, Debate”, in early March, for the election to be held on the 5th of May, it

was said that Panama’s unemployment rate at 7%, was far too high. Assuming all the 40,000 previously

employed, directly and indirectly, by Minera Panama are now unemployed, unemployment would now

only be only 5% were they still working. No meaningful options to replace these jobs were tabled in this,

or subsequent, presidential debates.

was said that Panama’s unemployment rate at 7%, was far too high. Assuming all the 40,000 previously

employed, directly and indirectly, by Minera Panama are now unemployed, unemployment would now

only be only 5% were they still working. No meaningful options to replace these jobs were tabled in this,

or subsequent, presidential debates.

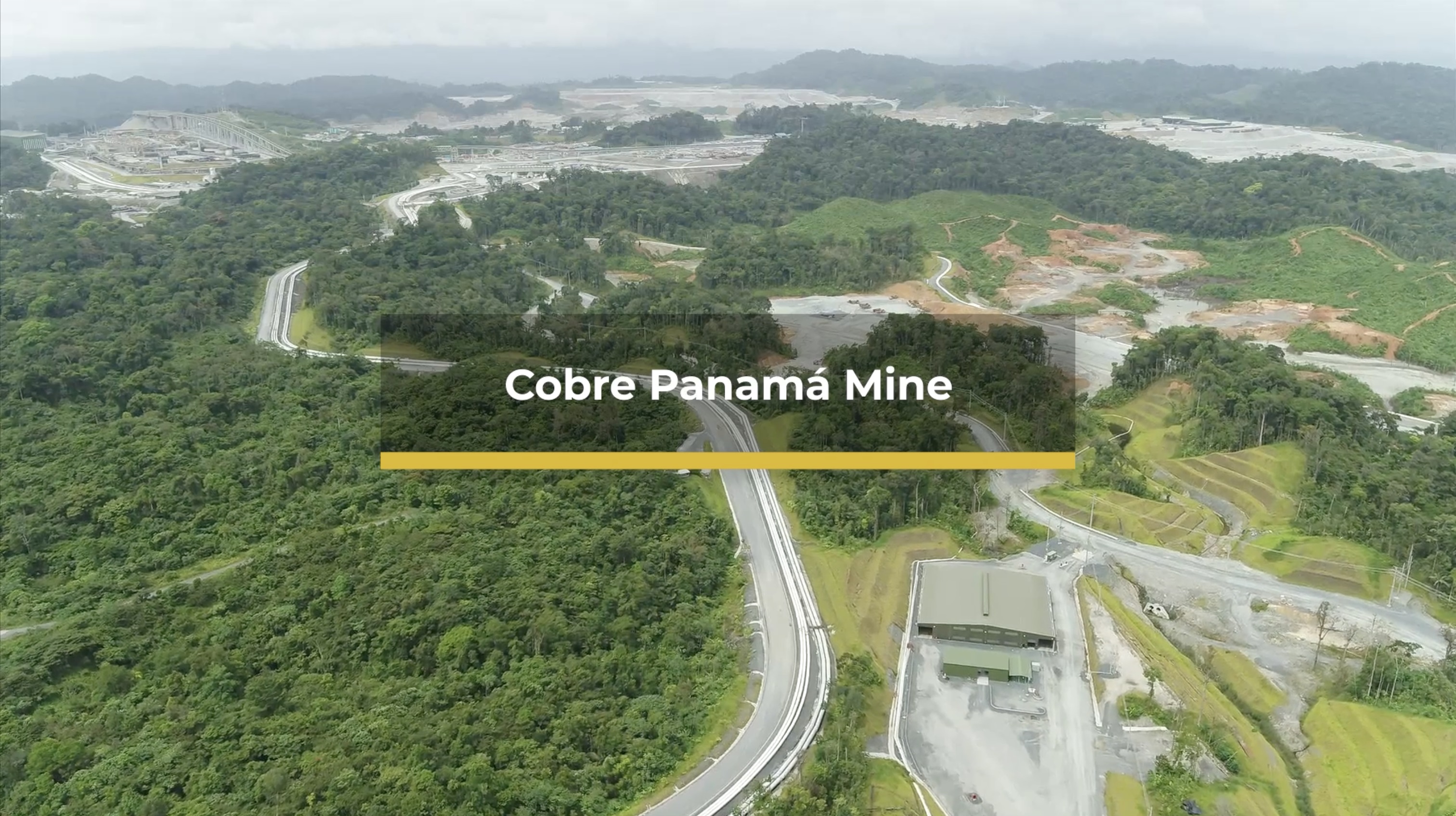

The copper deposit produced by FQM was first identified in 1968 by a United Nations

Development Programme field survey, with some holes drilled in 1969 to support an estimate of the

reserves. The project then passed through various hands, ending up with FQM in 2013. Following mine

construction, at a cost of some 10 billion US, including a new port on the Caribbean, and a new road

across the isthmus, copper concentrate production started in 2019.

Development Programme field survey, with some holes drilled in 1969 to support an estimate of the

reserves. The project then passed through various hands, ending up with FQM in 2013. Following mine

construction, at a cost of some 10 billion US, including a new port on the Caribbean, and a new road

across the isthmus, copper concentrate production started in 2019.

The Cobre Panama mine, in the mountains, in Colon province, near Coclesito, can best be

accessed via a drive northwards, of little more than one hour, from Penonome, which is located on the

InterAmerican Highway. It is the largest new open pit copper mine in the World, employing, in mid-

2023, some ten thousand directly, and thirty thousand indirectly. Daily sales were approximately $10

million US, circa half of which remained in Panama as salaries, taxes, local purchases of goods and

services etc. In 2022 the mine was responsible for circa 1% of the World’s copper production, 5% of

Panama’s GDP, 75% of Panama’s exports of physicals, 2% of Panama’s employment, and 40% of FQM’s

global revenue, with employment by Cobre Panama being an aspiration for many Panamanians.

Some of the income from the mine was used by employees to buy, or build, new homes, buy new

cars etc, with local contractors buying, for example, fleets of buses to transport FQM employees. Major

new housing developments, shopping malls etc were also started, mainly funded by bank loans, in

expectation that the flow of cash from the mine would continue, with FQM’s contract specifying a 20 –

40 year mine life. Some of these projects now appear to be “on hold”.

cars etc, with local contractors buying, for example, fleets of buses to transport FQM employees. Major

new housing developments, shopping malls etc were also started, mainly funded by bank loans, in

expectation that the flow of cash from the mine would continue, with FQM’s contract specifying a 20 –

40 year mine life. Some of these projects now appear to be “on hold”.

Anti-mining protestors took to the streets in late-2023, with identifiable groups of protestors

including members of the construction workers union SUNTRACS, teachers, indigenous groups and

students, none of whom would appear to have been impacted by Minera Panama’s operations, or likely to

be in the future, except via increased government expenditure, on such things as education, pensions,

medical care etc. Following months of popular protests, during which the InterAmerican Highway and

major roads in Panama City were closed, vegetables rotted in the backs of trucks as they could not be

transported from the producers to the city, no bananas in the supermarket, schools and businesses closed,

many losing their employment, at a daily estimated cost of $200 million to the economy, and Cobre

Panama workers counter-demonstrating to “Save Our Jobs”, it appeared, in November as though there

were two options open for Panama. First was for the economy to continue to be partially closed-down,

and for Minera Panama to restart copper production as usual. The second was for the government to

impose closure on the mine, and for the rest of the economy to revert to business as usual. The Supreme

Court judgement in late-November closed the mine, on the grounds that the contract under which it was

operating was “unconstitutional”. However, that the demonstrators, and ultimately the government,

favored “business as usual”, to keep the shops full, the schools, roads and ports open etc, should not

necessarily be taken as evidence that “the people have spoken” in favour of mine closure per se.

With so much apparently at stake, would it not have been better to renegotiate FQM’s contract so

as to conform with the constitution than close the mine?

Court judgement in late-November closed the mine, on the grounds that the contract under which it was

operating was “unconstitutional”. However, that the demonstrators, and ultimately the government,

favored “business as usual”, to keep the shops full, the schools, roads and ports open etc, should not

necessarily be taken as evidence that “the people have spoken” in favour of mine closure per se.

With so much apparently at stake, would it not have been better to renegotiate FQM’s contract so

as to conform with the constitution than close the mine?

It should be noted that though FQM’s contract terms allow the government to cancel FQM’s

contract, these terms call for “fair compensation” to be paid in this event. Should this go to international

arbitration, it will be likely be considered that it was primarily the government’s role to ensure that the

contract abided by the Panamanian constitution and other Panamanian laws, and that this would impact on

any judgement and award of compensation.

There are, however, a number of different reasons given for the mine being closed, in addition to it

being “unconstitutional”.

First, the objections to environmental damage caused by the mine. However, more jungle is

trashed in Darien every year, legally and illegally, than the mine will need in total. In Darien, typically the

jungle is trashed, and the big tree trunks hauled away. At Minera Panama, the jungle is cleared and a five

hundred metre deep pit is planned, to be dug out over a period of perhaps ten years, to take the copper out,

delivering much more value and income for the collateral environmental damage. FQM have a plan,

approved by the government, for refilling these pits, using tailings from the process plant and material

from later pits, in anticipation of restoring the site. FQM have already cleared enough jungle to allow the

first pit to be worked out, allowing a further maybe ten years of copper production with no more

significant environmental damage. Closing the mine now, to limit environmental damage, would not

appear to be cost-efficient.

Second, there has been a long-ongoing, and public, negotiation between FQM and the

Panamanian government, as to how much tax FQM should pay, perhaps exacerbated by a less than

“sensitive” approach by FQM and lack of experience and knowledge on the government side as to how

such things are customarily analyzed by international mining companies. This has left the public with the

impression, rightly or wrongly, that FQM are not paying enough.

Third, it is said that pollution from the mine has caused an increase in cancer in children in Cocle.

However, there is no evidence to support this assertion, and with the mine on the other side of the

mountains from Cocle, in Colon Province, it is unlikely that any run-off from the mine would have

reached Cocle anyway.

However, there is no evidence to support this assertion, and with the mine on the other side of the

mountains from Cocle, in Colon Province, it is unlikely that any run-off from the mine would have

reached Cocle anyway.

Fourth, it is said that pollution from the mine is entering Lake Gatun, on the Panama Canal, thus

polluting Panama City’s water supply. However, the Panama Canal Commission has said publicly that

no run-off from the mine is reaching the watershed of the Canal, as there are several river valleys crossing

the potential route.

Fifth, this same argument negates the claim that the mine is “stealing” the Canal’s water.

Sixth, various communities are complaining that FQM has promised them roads, school, clinics

etc which have not been built. But, in reality, FQM is not in the business of committing to such works,

which have likely been promised by government using income from the mine, but not yet delivered.

etc which have not been built. But, in reality, FQM is not in the business of committing to such works,

which have likely been promised by government using income from the mine, but not yet delivered.

Seventh, it is said that the vast majority of workers at the mine are foreigners, not Panamanians,

which would be illegal. This is untrue, and likely based on observations by someone who has never been

to the mine site.

which would be illegal. This is untrue, and likely based on observations by someone who has never been

to the mine site.

Eighth, it has been claimed that the run-off from the mine is killing the fish in the rivers.

However, an under-water camera survey in early-2023 showed healthy fish swimming in the river just

down-stream of where the waste water entered it.

And there is more………..

Though such assertions have been voiced loudly and publicly, when these are shown to ignore the

evidence, these assertions are never retracted, and the evidence almost never made public – so these

assertions are still all out there.

It is understood that several groups appointed by the government, including international mining

consultants, have been to the mine but have failed to find any “smoking guns” with respect to the

environment or other issues discussed above. However, a delegation from Chile reported that it would

take some twelve months to develop an environmentally-acceptable plan to abandon the mine, and maybe

ten years to implement it – things for which the government has neither the, circa $1 billion, funding nor

expertise.

SUNTRACS, the trades union for Panama’s construction workers, the most active of workers’

formal representatives in Panama, customarily in the van of almost any significant industrial action, such

as demonstrations, strikes, road closures etc, organized demonstrations and strikes that delayed

construction of the mine in 2016. Subsequently SUNTRACS were unsuccessful in their bid to represent

the workforce during the mine operations phase, with FQM and their employees setting up UTRAMIPA,

to represent the mine workers only. SUNTRACS, whose members were minimally impacted by the mine

operation, were the most visible and effective organizers of the demonstrations, road closures, port

closures, rail closures etc in late-2023, and were prominent in negotiations with government. It has been

suggested that SUNTRACS, having been previously spurned by FQM and their employees, may be

pursuing a vendetta against them. As foreseen at the time, mine closure has negatively impacted

construction projects in Panama, with a resulting reduction in demand for the construction workers that

constitute the majority of SUNTRACS’ members. Industrial action by one trades union, to put forty

thousand others, many members of another trades union, out of work is unusual, to say the least!

Many Panamanians report that the principal driver of mine closure is the anger felt by the

Panamanian people against the politicians whose corruption, and theft from the public purse, is perceived

as having recently increased to a new, unacceptable and unsustainable, level. Though killing the goose

because some of the golden eggs are being stolen may not be a logical response to this, this may well be

what the people want.

FQM made almost all of its employees redundant in December, and the mine is currently not

producing. However, the mine remains, with almost one thousand workers on site, for “care and

maintenance”, and to monitor for and prevent any leaks to the environment etc, at cost of some $20

million per month. FQM are funding this, in the hope that they may be able to start production again some

time after the May 5 th election.

Should the mine remain closed, then Panama will lose some forty thousand good, mainly

unionized and tax-paying, jobs and five million dollars coming into Panama every day. Fitch has already

reduced Panama’s credit rating to “Speculative” (“Currently highly vulnerable to non-payment, default

has not yet occurred, but is expected to be a virtual certainty”). This has increased Panama’s cost of

borrowing, and will make it much more difficult, and costly, for the government to borrow money, and for

the government and commercial companies to finance new projects in Panama.

borrowing, and will make it much more difficult, and costly, for the government to borrow money, and for

the government and commercial companies to finance new projects in Panama.

Though FQM have made it clear that they hope the mine will re-open, with FQM in charge, they

have also made it clear that they will be seeking “Fair Compensation” if it does not. In December it was

reported, quoting a lawyer with knowledge of such things, that fair compensation: would be “at least $50

billion”, a sum for which the Canal tolls would barely pay the interest on the capital sum, and equivalent

to some $50 thousand for each household in Panama. FQM is reported to be already seeking $20 billion

compensation under the Canada-Panama Free Trade Agreement, with proceedings in Miami. It is

understood that this may be only one of the claims to be made, with the total nearer to $50 billion.

Whether $20 billion, or $50 billion, equivalent to almost two thirds of Panama’s annual GDP, it is

unlikely that Panama can readily pay such a sum, leading the government into unknown territory, possibly

resulting in the USA retaking control of the Canal, to keep it operating efficiently.

Reuters reported on 18 th of April that “Panama election unlikely to shift Outcome for First

Quantum’s Copper Mine”, mainly because none of the eight presidential candidates for the 5 th May

election would openly support reopening the mine, such support being perceived as a “third rail” for

anyone seeking election. Reuters also quoted the leader of SUNTRACS as saying that “There was no

scenario under which they would let the authorities seal a new deal with First Quantum”.

However, once the new president occupies his office and “opens the books’, the combination of

little money in the bank, huge loans, much increased during the current administration, higher interest

payments due to downgrading of Panama’s credit rating, the likelihood of huge “fair compensation”

payments being awarded against Panama, the cost of abandoning the mine in an environmentally-

acceptable manner, newly-unemployed mine workers and others dependent on the mine wanting jobs, and

many groups expecting the delivery of the costly goodies promised to them while he was on the election

trail, may present a most unattractive, and likely apparently irremediable, prospect. And, of course,

especially in Panama, it is no fun being president with no money to hand. This might lead him to

consider, how, for example, an (international mining) company could be awarded a, perhaps ten year,

contract for abandoning the mine, but allowed to produce and sell only enough copper to pay its own

costs, with no income for the government. After a few years, when the teachers, pensioners et al have had

no pay increases, new construction projects have dried up etc, and unemployment is at a new “high”, then

there would likely be popular support for reverting to full mine production, to provide the government

with funds to cover these, and other, costs and to get the economy expanding again.

If this does not happen, then the resulting dearth of new investment in Panama, and the associated

shortage of high-quality, export-oriented, employment opportunities, may impoverish generations of

Panamanians.

Panama Wednesday April 24 of 2024

George Bauer is the pen name of a retired mining engineer, resident in Panama for over twenty years.

George Bauer is the pen name of a retired mining engineer, resident in Panama for over twenty years.